|

“‘Getting Up Cows,’ that’s what it’s called, ‘Getting Up Cows,” William Adams said. “An old fella played that. He was a cracker-jack old fiddler, though, I don’t believe he could beat me….” Mike Seeger hadn’t come to the neighborhood to record Adams initially, but now he wanted to hear any tune the Black fiddler could remember, even if he forgot it halfway through or couldn’t remember the name. “I forget how that goes, though, I haven’t played that since a long time ago,” the 72 year-old Adams continued before he put the bow on the fiddle’s strings and hesitantly pulled the tune from deep in his memory. In the end, it sounded like he might have just last played it a week or a year ago, not some 20-odd years earlier.

This field recording wasn’t taken in some rural hamlet or deep holler, it was less than five miles from Seeger’s home in the well-to-do suburb of Chevy Chase outside Washington, D.C. And yet in 1953, when Seeger stepped into Adams’s neighborhood of KenGar, segregation left this community so separate from the white towns and neighborhoods surrounding it, a white person might drive by without even knowing it was there.

8 Comments

Read my profile of Eli Smith on OZY.

Check out my new piece on OZY about El Hadj Sidikida Diabate, his sons, and the start of Guinean National Orchestras in West Africa.On January 15, 1959, Sidikiba put together the first Guinean national orchestra, the Syli National Orchestra. The played at international festivals, including this one in 1969. Check out more music and stories of the Guinean orchestras here on the blog.It's October! That means we can start with Halloween-themed posts, right? I was recently made aware of the fact that there are a number of sheet music covers with witches in the Lester S. Levy Collection at the Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries Special Collections. So just in time for Halloween, I'll share some of them here!

At this year's 19th Century Banjo Gathering (Banjo Collector's Gathering), Pete Ross and I presented on Levi Brown.

Our research uncovered that there was much more to Brown's life than just making banjos, which make sense when you know a little bit about existing Minstrel-Era banjos.

Julia Margaret Cameron's ethereal photographs were born out of a gift from her daughter and son-in-law in 1863. The camera was meant to amuse her, but she soon began to take photography as a serious pursuit. Her portraits are often close up, with a soft glow, and often with props that evoke a theatrical performance. She was making art in the style of the Pre-Raphaelites at a time when most photographers were simply doing studio portraits for profit. In these two images, from 1874 and 1875, Cameron's subjects are holding a piccolo-sized five-string banjo. The banjo is piccolo-sized (smaller than a regular banjo), fretless, and the skin head is attached with tacks, rather than tightening hardware that became more common in the 1880s and 1890s.  "Tears from the depth of some divine despair." Julia Margaret Cameron, 1875. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. "Tears from the depth of some divine despair." Julia Margaret Cameron, 1875. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The banjo is thought of as a quintessentially American instrument, but it first sprang into American pop culture in the 1840s as black-face minstrel performers took the African instrument on stage, using it to simultaneously mock and idolize African culture. Not long after the craze overtook the U.S., minstrel performers brought their music to England. The "Father of Minstrelsy" Joel Walker Sweeney first performed in London in 1843, and was so successful that he continued to perform all over England, and groups of minstrel players that were forming in the U.S. went on tour across Britain. By the 1860s, the British had their own minstrelsy tradition, with Englishmen forming their own troops and even publishing banjo instructional methods. The U.S. had a tradition of banjo playing among free and enslaved African Americans long before the minstrel show. Sweeney said he learned from slaves on his father's plantation, and while some of the traditional American banjo music of today comes from minstrel show music, there is also a tradition that comes from the African American music that predated minstrelsy or happened concurrent with the minstrel era. But no such tradition existed in England, so the banjo remained something for the stage and parlor, and Cameron's use of the banjo as a prop reflects this.

For more information on Julia Margaret Cameron, visit the Victoria and Albert Museum's website or the page for the recent exhibit of Cameron's work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For more information on the banjo in England during this time, read the article by Bob Winans and Elias Kaufman in American Music here.

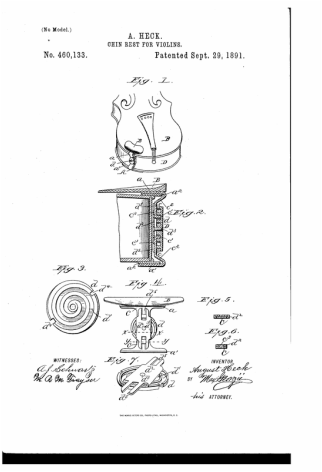

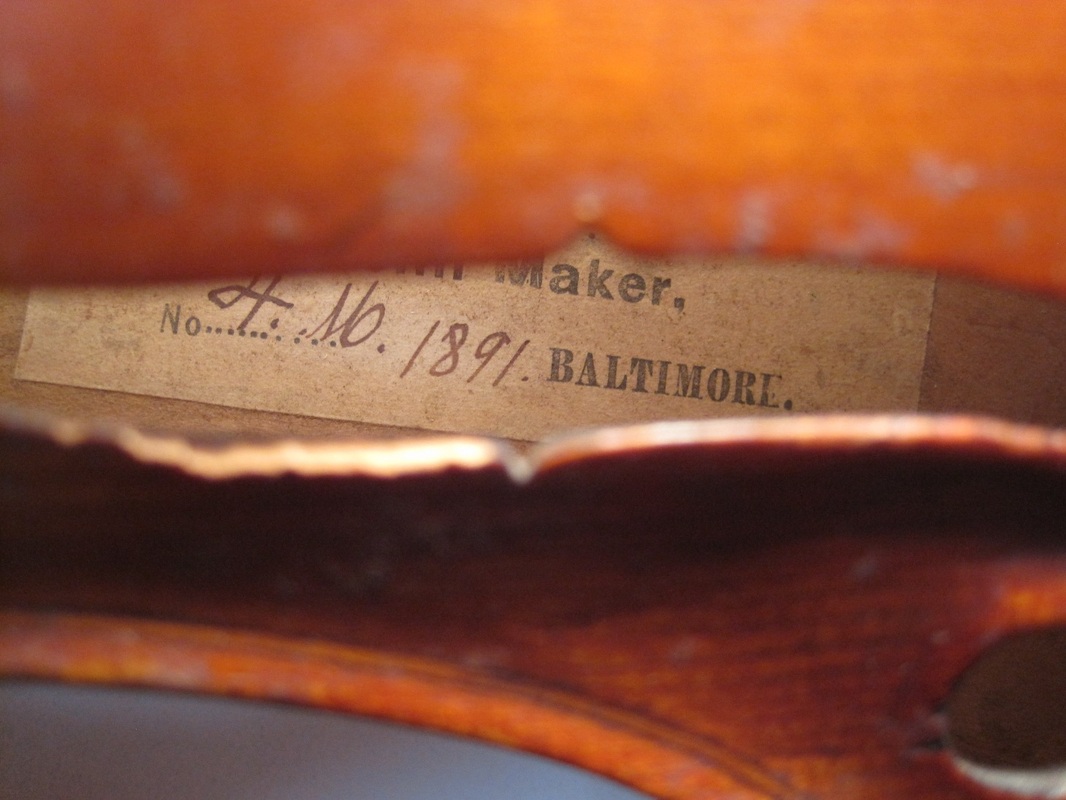

A friend and luthier, Andy FitzGibbon sent me these images of a fiddle made in Baltimore by a man name August Heck. Baltimore once had a vibrant instrument making scene, and I wondered if Heck was part of that. Heck was born in Germany in 1847 and emigrated to the United States in 1884, during the second large wave of German immigration. The first large flow came in the 1850s, after the 1848 revolution forced many liberals out of the country. In the 1880s, more than one million Germans resettled in the United States, many escaping religious prosecution and military service. Baltimore had a large German population from every wave of immigration, and German instrument makers like William E. Boucher, Jr. and C.H. Eisenbrant had very successful businesses.  We can track Heck a bit by the locations on his labels. Violins #74 and #77 turned up with "Heckville, Indiana," while an advertisement listed him later in Valparaiso, Indiana. By 1891, he was in Baltimore and by 1900, he's listed in the Washington, D.C. census as an instrument maker. While in Baltimore, he even filed a patent. "A chin rest for violins" is patented by August Heck, of Baltimore, which is the combination with a clamp having lips for embracing the violin, of a clamping twin button whose plant of motion is at a right angle with lips.  The language from the newspaper isn't too clear. Basically, his invention featured a round gear that screwed to tighten a chin rest on the top and bottom of the fiddle. Most chin rests need a little key to tighten two rods that connects the top (the chin rest) with another metal piece on the bottom of the fiddle. Industrialization meant innovation and everyone wanting to patent their million dollar idea. Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and Nikola Tesla did have lots of good ideas that they patented, and they were rewarded for it. Thousands of others followed their lead. In the 1880s, the boom really took off when inventors no longer had to create a model of their patent. All they had to do was have an idea, a description of how it worked, and a drawing. By the end of the century, 700 to 800 patents were being filed each week. Since Heck only needed the idea and a drawing, there is no guarantee that any of these chin rests were actually ever made. Heck moved around quite a bit. He had lived in at least three states after having only been in the United States for 16 years, and seemed to be constantly chasing his fortune. From Washington, D.C., he may have moved to Los Angeles where he's listed in the 1920 census as a 73 year old man, but still an instrument maker.

|

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed