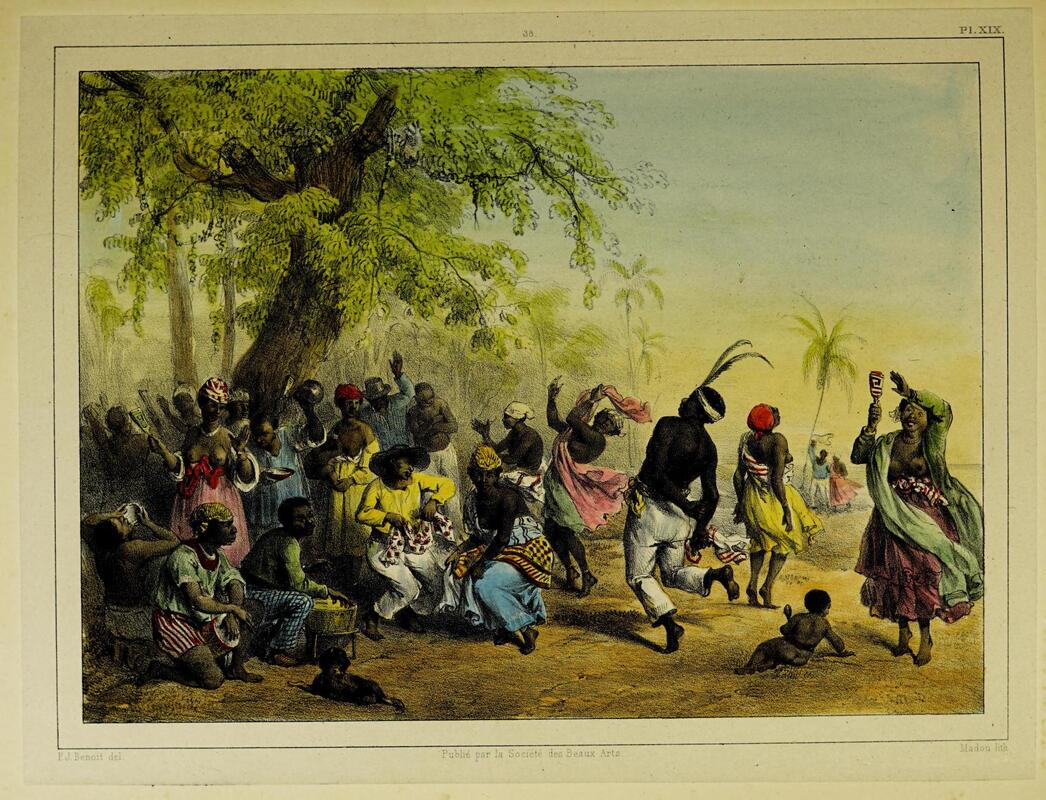

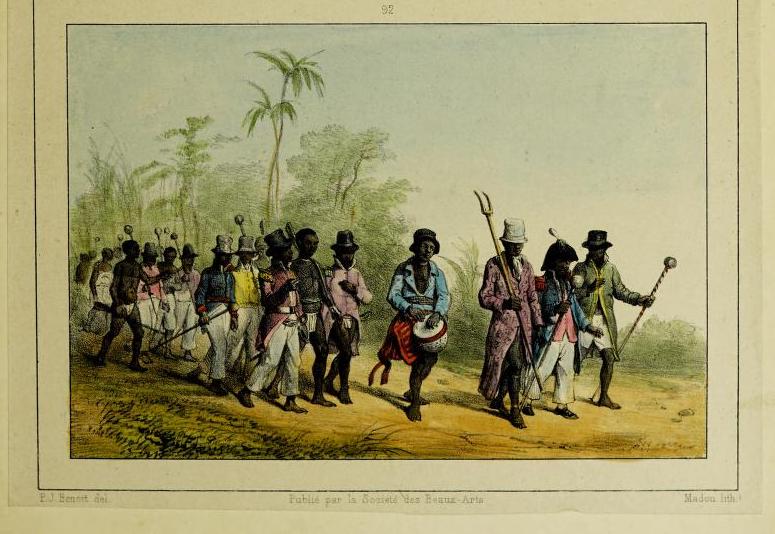

At the beginning of my research, I was interested by the Indians seemingly close connections to other traditions that I had researched where the banjo did appear, like Junkanno (John Canoe) and Carnival in the Caribbean. In my previous blog post, I wrote about the Backstreet Cultural Museum and Mr. Sylvester Francis’s work to preserve the costumes of the Mardi Gras Indians. When I talked with my friend Tom Piazza about wanting to see the Indians as part of my research, he said that while they come out at Mardi Gras, St. Joseph’s night and the Sunday before were really the time to see them. After I saw them and continued to see references to similar outfits and processions in the Caribbean, I couldn't help thinking that this was a shared tradition, even if the specific evidence for how it was shared hasn't been well documented. Many suits today “more explicitly reference Native American culture,” as Cynthia Becker writes, but the Spirit of Fi Yi Yi and the Mandingo Warriors “incorporate materials associated with African art, such as raffia, kente cloth, and cowrie shells, and include face masks and African-inspired shields” [1]. Throughout the written history of New Orleans after Africans were forcibly brought to the city, we see descriptions of the costumes that free and enslaved people of African descent wore as they danced in and around the city. These historical descriptions don’t always conjure the structured, beaded outfits that the Mardi Gras Indians wear today, but traditions change. Christian Schultz visited New Orleans in 1808, and when he saw dances at the back of the city, where Congo Square is today, he wrote that the “principal dancer or leaders are dressed in a variety of wild and savage fashions, always ornamented with a number of the tails of the smaller wild beasts”[2]. More than 100 years earlier, when Hans Sloane was in Jamaica at a festival, he noted that the dancers “very often tie Cows Tails to their Rumps, and add such other odd things to the Bodies in several places, as gives them a very extraordinary appearance”[3]. In 1817, two years before Latrobe observed a banjo in New Orleans, German Johann Ulrich Buechler wrote that on Sunday afternoons, “behind the city” (meaning up from the river), Black residents gather to dance. The men “wear Oriental and Indian outfits, with a Turkish turban of different colors, red, blue, yellow, green, and brown, and also matching scarves around their waists to cover their nakedness” while the women dress in the newest fashions [4]. In other words, they are elegant. When I read this, I thought of an image from Suriname done by P.J. Benoit, where the fabrics flow freely as men and women dance. In a Vodou ceremony in Haiti a few years before 1817, Drouin de Bercy describes men with “leaves around their loins, feathers on their heads, and bows around their wrist,” who are part of the ritual to intiate new members [5]. Around the same time, Timothy Flint wrote about the “Congo-dance” performed around New Orleans. “Some hundreds of negroes, male and female, follow the king,” who wears a crown made of “oblong, gilt-paper boxes on his head, tapering upwards, like a pyramid. From the ends of these boxes hang two huge tassels, like those on epaulets.” This is more evocative of the structured headpieces worn by Indians, but also reminds me of descriptions and images of Junkanoo. Flint continues that the people who follow in the parade behind the king wear “their own peculiar dress” with streams and bells that tinkle [7]. Leon Beauvallet describes something similar during Dia de Los Reyes (Epiphany) in Havana, Cuba in the 1850s. The genuine king wore “a very proper red, close coat, velvet cest, and a magnificent gilt paper crown.” Next to him was his queen, while behind him were bands of men, some of who were dressed as Native Americans and others who had “large yellow spots” drawn all over their bodies, “magnificent peacock feathers” in their hair and flour on their faces [8]. In 1831, Frenchman Pierre Forest wrote about a dance on the edge of Lake Pontchartrain, where the Black people gather in smaller groups: “Each company has its flag, which, perched at the top of a pyramid-shaped pole, serves as a rallying point for all the parties” [9]. In Haiti almost ten years later, Victor Schoelcher noted that during Carnival, groups of Black men paraded while singing and dancing. The men had outfits made of a hundred pieces of striped or checkered cloth, and the “king wears a feather turban as his crown.” Each company also had its own name and flag [10]. Today, the New Orleans Indians have a Flag Boy, who carries the tribe’s symbol or name. During a public “Congo Dance” in 1843 when a reporter from the Times Picayune was able to attend, the leader of the orchestra strummed “a long-necked banjo, the head of which was ornamented with a bunch of sooty parti-colored ribbands,” and the male dancer wore “a pair of leather knee caps from which were suspended a quantity of meal nails, which made a jingling noise that timed with his music” [11]. It’s not until 1860 that James Creecy again associates the dances in Congo Square with the banjo, writing that “colored people and negroes, bond and free, assemble…with banjos, tom-toms, violins, jawbones, triangles, and various other insturments.” He, too, writes that the dancers wear “fringes, ribbons, little bells, and shells and balls, jingling and flirting about the performer’s legs and arms”[12]. Scholar Jeroen Dewulf sees a commonality between these costumes and Iberian Moresca dances where dancers “typically wore gilt paper helmets, long streamers tied to their soulders, and bells to their legs”[13]. But worn percussions instruments are common across Africa, and in African Art in Motion, Robert Farris Thompson explores the masks, headdresses, and elaborate costumes worn by dancers in many African cultures [14]. In Flash of the Spirit, Farris Thompson explains that feathers are common decorations in Kongo costume and “connote ceaseless growth as well as plenitude”[15]. The origins of the Mardi Gras Indians aren’t clear. There are clear connections to various African traditions (how could there not be?). But the term Indian and the elaborate feathers and beading evoke Native American dress, although many people point out that its not the dress of Native Americans who lived around Louisiana. Michael P. Smith argues that, “Despite the lack of specific genealogical records, the black Indian gangs of New Orleans descend both spiritually and culturally, and, according to oral history, by direct ancestry from these renegade, underclass groups in French and Spanish colonial New Orleans”[16]. That is to say, they descend from Maroons or enslaved people who escaped bondage and lived in the swamps outside of the city and may have been aided and formed new communities with Native Americans in the area. The costumes may have been an ode to the Native American communities that sheltered enslaved runaways. Cynthia Becker (and others) point out the potential influence of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows on the costumes. What masking Indians wore could have also been a more “politically safe strategy” for representation of “African ceremonial memories,” as Richard Brent Turner writes [17]. Ned Sublette writes that “The closest resemblance to the motifs of the Indians' suits might be in Trinidad, where the Carnival tradition derives largely from a French Creole population,” although there is “no evidence for any direct influence” between the traditions [18]. Trinidad was a mix of African, European, and Amerindian cultures, just like New Orleans and much of the Caribbean. The historical record doesn’t give us a perfect line for where the traditions of the masking Indians came from, but I loved that moment when I came across a description of a king, parade, or outfit for a dance that reminded me both of a historic description somewhere else in the Americas and a contemporary tradition. One of the points that I come back to in Well of Souls and research into early Black music and dance is that we have to think of the Americas as a more continual space. A place where people moved—by choice and force—and cultures mixed and blended, and where we can see cultural throughlines if we choose to look for them. Sources: [1] Cynthia Becker, "New Orleans Mardi Gras Indians: Mediating Racial Politics from the Backstreets to Main Street," African Arts Vol. 46, No. 2, Performing Africa in New Orleans (Summer 2013), pp. 36-49. [2] Christian Schultz, Travels on an Inland Voyage through the states of New-York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee : and through the territories of Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi and New-Orleans; performed in the years 1807 and 1808; including a tour of nearly six thousand miles (New York: Isaac Riley, 1810), 197. [3] Hans Sloane, Voyage to Jamaica..., xlviii-xlix. [4] Johann Ulrich Buechler, Land und Seeriesen eines… 1820 [5] Drouin De Bercy, De Saint-Domingue: de ses guerres, de ses révolutions, de ses resources, et de moyens a prendre pour y rétabilir la paix et l'industrie (Paris, 1814). [6 & 7] Timothy Flint, Recollections of the Last Ten Years, Passed in Occasional Residences and Journeyings in the Valley of the Mississippi, from Pittsburg and the Missouri to the Gulf of Mexico, and from Florida to the Spanish Frontier (Boston: Cummings, Hilliard, 1826), 139-140. [8] Leon Beauvallet, Rachel and the New World: A trip to the United States and Cuba (New York, 1856), 363-365. [9] Pierre Forest, Voyage aux Etat Unis (Lyon: Perret, 1834). [10] Victor Schoelcher, Colonies étrangeres et Haïti (Paris: Pagnerre, 1843), 299. [11] "THE CONGO DANCE” 18 Oct 1843 Times Picayune. [12] James Creecy, Scenes in the South and Other Miscellaneous Pieces (Washington: Thomas McGill, 1860), 19-22. [13] Jeroen Dewulf, “From Moors to Indians: The Mardi Gras Indians and the Three Transformations of St. James,” Louisiana History vol 56, no. 1 (2015): 11 [14] Robert Farris Thompson, African Art in Motion (University of California Press, 1979). [15] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), 121. [16] Michael P. Smith, “Behind the Lines: The Black Mardi Gras Indians and the New Orleans Second Line,” Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1, Selected Papers from the 1993 National Conference on Black Music Research (Spring, 1994), 45. [17] Richard Brent Turner, p. 55 [18] Ned Sublette, The World that Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square (Chicago: Lawerence Hill Books, 2008), 298. This is part of Banya Obbligato, a series of blog posts relating to my book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. While integrally related to Well of Souls, these posts are editorially and financially separate from the book (i.e., I’m researching, writing, and editing them myself and no one is paying me for it). So, if you want to financially support the blog or my writing and research you can do so here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed