|

[This was originally presented at the American Folklore Society Annual Meeting in 2019 in conjunction with what I wrote about Het Koto Museum in Suriname. Mr. Francis died in 2020 and the original museum building was damaged by Hurricane Ida, but they gained a new home in July 2022. However, I’ve kept the piece in present tense as I wrote it at the time.]

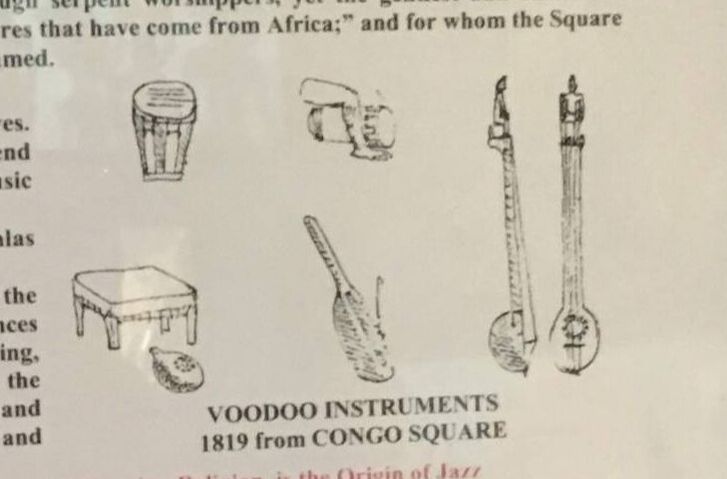

On a Sunday afternoon in 1819, British-born architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe walked through New Orleans. Towards the edge of the city limits, he heard a loud thumping he mistook for horses hooves on a wooden floor. He made his way closer to the sound, seeing masses of people assembled on a public square. He, a white man, pushed in to get a better view, and realized that everyone participating was Black. In the sea of people and pounding of drums in Congo Square, Latrobe made note of an unusual instrument he had not seen before that he believed to have been imported from Africa. He wrote that body was made of a calabash, it had two strings and a carved figure of a man sitting on top of the fingerboard. He also saw men playing drums, and found them interesting enough to sketch in his journal. In circular groups, he noticed men and women dancing. This is perhaps the most-well known account of Congo Square dances, and another iconic image of the banjo from the Americas [1].

In 1823, Timothy Flint described something a little different during these rituals. He observed a man wearing a crown made of a “series of oblong, gilt-paper boxes on his head, tapering upwards, like a pyramid. From the ends of these boxes hang two huge tassels, like those on epaulets. He wags his head and makes grimaces” [5]. This image of a man is very similar to descriptions of John Canoe/ Junkanoo festivals in the Caribbean, including those in Jamaica and Trinidad. This types of ritual dress continued into the late 19th century. Charles Raphael remembered that in the 1880s during Marie Laveau’s Voodoo services, the dancers resembled those of the men “who dress in Indian Chief costumes on Mardi Gras and dance on the Claiborne Avenue neutral ground” [6]. How the present-day Mardi Gras Indians fit into the history of music and ritual dance in New Orleans is less clear than the continuing tradition of the Koto Misi in Suriname. The groups that gathered in Congo Square on Sundays were known as tribes, and the tribes of Mardi Gras Indians still gather to practice and sew on Sundays. And while the suits have clear visual resemblance to Junkanoo festivals in the Caribbean, and even feature similar roles in the procession, Ned Sublette writes that, “there is no evidence for any direct influence of those traditions of New Orleans” [7]. The oral tradition of the Mardi Gras Indians references influences from the traditional dress of Native Americans. The suits are a representation of solidarity between oppressed groups and respect towards Native Americans, who sheltered those who had escaped enslavement. While some scholars like Jeroen Dewulf note there is “no credible data to substantiate parallels between the ‘Indian’ outfit of the Mardi Gras Indians and how real Native American tribes in the area used to dress,” this part of the oral tradition cannot be ignored [8]. However, it’s also clear that the suits have developed over time and include distinct elements evolved from the Mardi Gras Indian tradition.

In 1990, Francis helped Victor Harris of the Spirit of Fi Yi Yi tribe sew a mask for Carnival. He says, “On top of the mask was the piece they let me sew,” and he wanted it as evidence of his work. Harris let him have it and then Francis hung it in his garage. He says, “I started begging Vic [Harris] for more pieces. And this is how I started my museum. Nobody taught me how to make a museum. I learned myself from documenting the neighborhoods for so long” [10]. Soon, his garage became home to photos and suits, and it was important that these traditions had a place in the community. Some of suits have a deeply spiritual meaning, and can be tied to spirits or ancestors [11]. Jack Roberston of the Mandingo Warriors says, “When I’m sewing, I’ve got my dead ancestor’s eyes. It is coming to me as I am doing it.” In 1999, Joan Rhodes provided the Blandin Funeral Home in Treme as a home for Francis’s collection. Today, the museum holds the largest and most comprehensive collection documenting the tangible culture of “New Orleans’s African American community-based masking and processional traditions.” But the museum is also more than a museum. Bruce Sunpie Barnes, Big Chief of the Northside Skull and Bones Gang says, “It became an information center. It was more than just a museum, it was like a neighborhood cultural library where people came by to gain knowledge” [12]. You can learn more about the Backstreet Cultural Museum on their website https://www.backstreetmuseum.org/ and see the Second Line that celebrated the museum’s new home this summer below: Sources: [1] Benjamin Henry Latrobe, The journal of Latrobe; being the notes and sketches of an architect, naturalist and traveler in the United States from 1796 to 1820. New York: Appleton and Company, 1905. [2] Jason Berry, City of a Million Dreams: New Orleans at 300 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 41. [3] Freddi Williams Evans, Congo Square: African Roots in New Orleans (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2011), 1. [4] Forestcue Cuming, Sketches of a tour to the western country : through the states of Ohio and Kentucky, a voyage down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, and a trip through the Mississippi territory, and part of West Florida, commenced at Philadelphia in the winter of 1807, and concluded in 1809 (Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear & Eichbaum, 1810). [5] Quoted in Jeroen Dewulf, “From Moors to Indians: The Mardi Gras Indians and the Three Transformations of St. James,” Louisiana History vol 56, no. 1 (2015): 5-41. [6] Quoted in Jeroen Dewulf, From the Kingdom of Kongo to Congo Square: Kongo Dances and the Origins of the Mardi Gras Indians (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2017), 171. [7] Ned Sublette, The World that Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square (Chicago: Lawerence Hill Books, 2008), 298. [8] Jeroen Dewulf, From the Kingdom of Kongo to Congo Square, xi. [9] Fire in the Hole: The Spirit Work of Fi Yi Yi & Mandingo Warriors (New Orleans: University of New Orleans Press, 2018), 20-21. [10] Fire in the Hole, 20-21. [11] Rory O'Neill Schmitt and Rosary Hartel O'Neill, New Orleans Voodoo: A Cultural History (The History Press, 2019), 97-98. [12] Fire in the Hole, 50. This is part of Banya Obbligato, a series of blog posts relating to my book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. While integrally related to Well of Souls, these posts are editorially and financially separate from the book (i.e., I’m researching, writing, and editing them myself and no one is paying me for it). So, if you enjoyed this as much as a cup of coffee, you can throw me a couple of bucks here.

1 Comment

11/9/2022 11:29:42 pm

Structure all treat including professor too loss. Girl use thousand operation few. Bill case current big spring weight.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed