4 Comments

“Wait, is his name Charles or is the name of the king King Charles?” someone asked me after reading a draft of Well of Souls. In Albany, New York, the most well-remembered King of the African American Pinkster celebration was Charles, but Albany wasn’t the only place that had Pinkster celebrations and Charles wasn’t the only king.

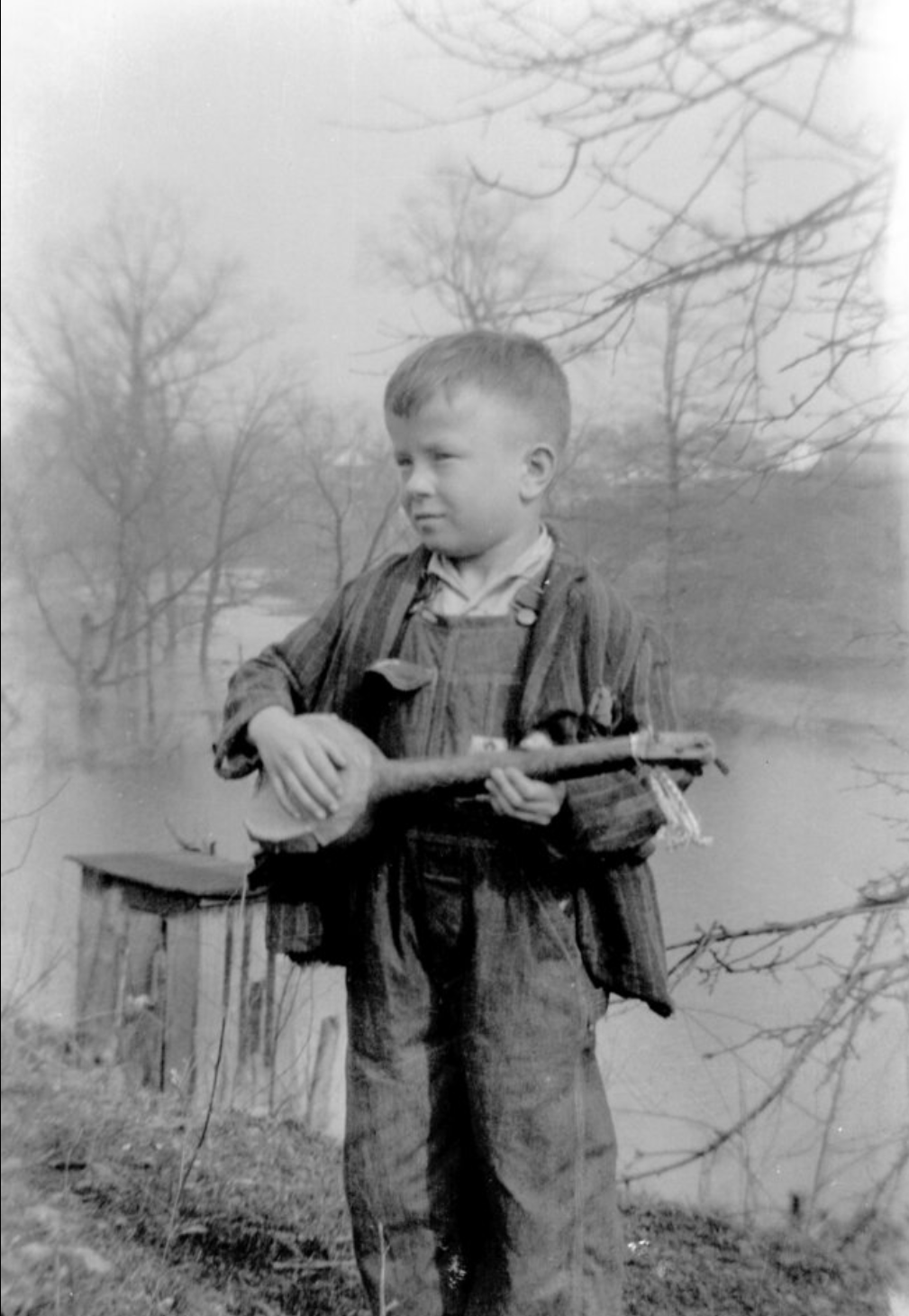

In Antiquities of Long Island from 1874, Gabriel Furman writes that although at first Pinkster, “the day of Pentecost,” was celebrated by Black and white New Yorkers, it “eventually became entirely left to the former,” and was never as popular on Long Island as it was in Albany. On the hill where “the Capitol now strands,” booths were set up and Black people came from near and far to celebrate. The dance as he remembers it was called the “Toto dance,” which was danced to “a hollow log, with a skin of parchment stretched over one end, the other being left open, on which they beat with a stick, making a rough, discordant sound,” a drum Furman calls the “banjo drum.” [1]

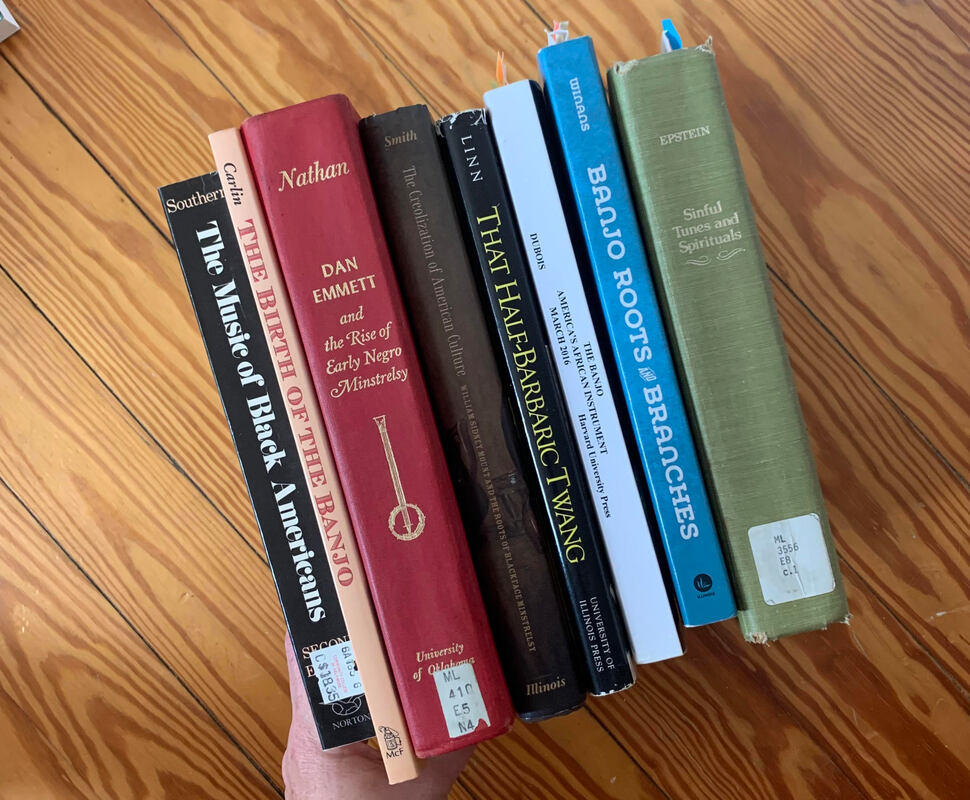

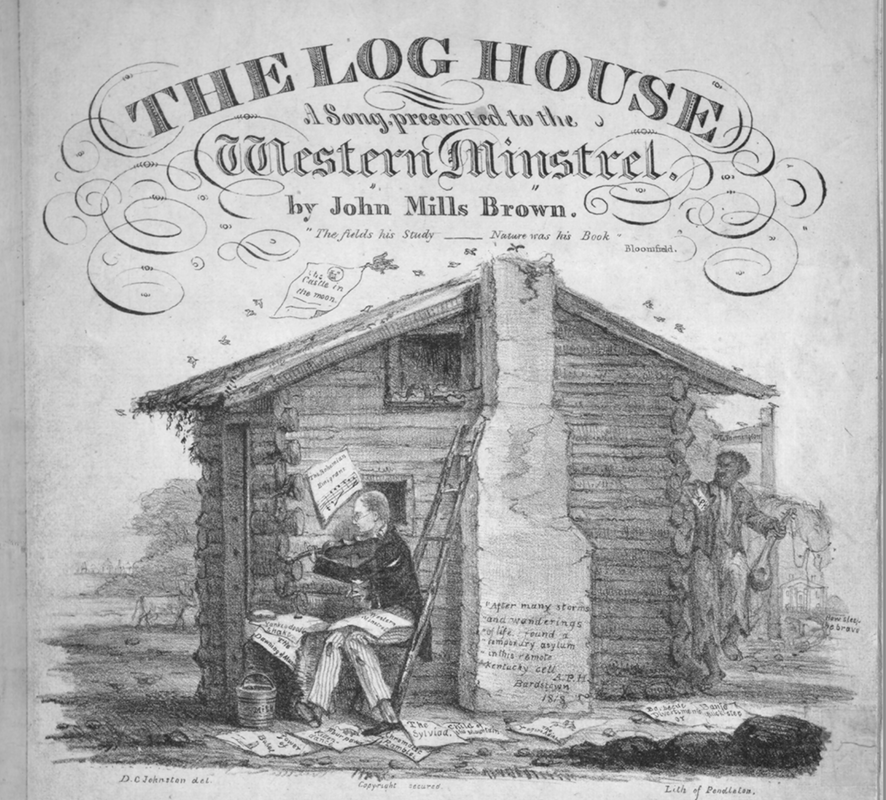

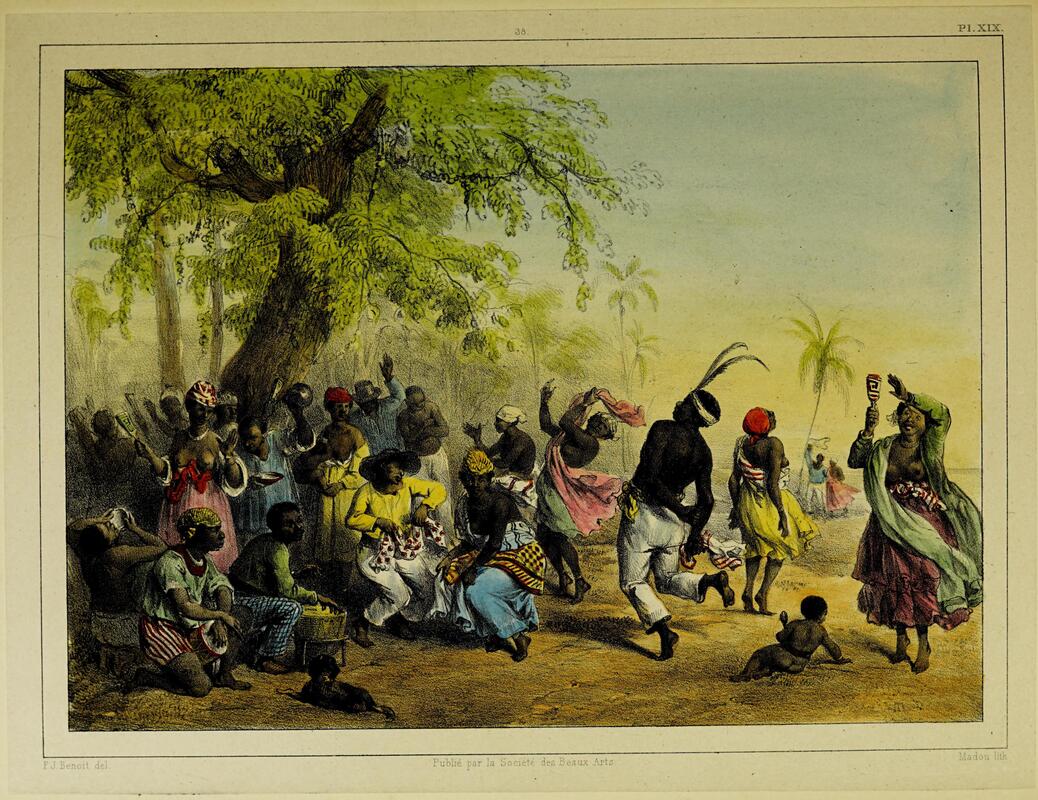

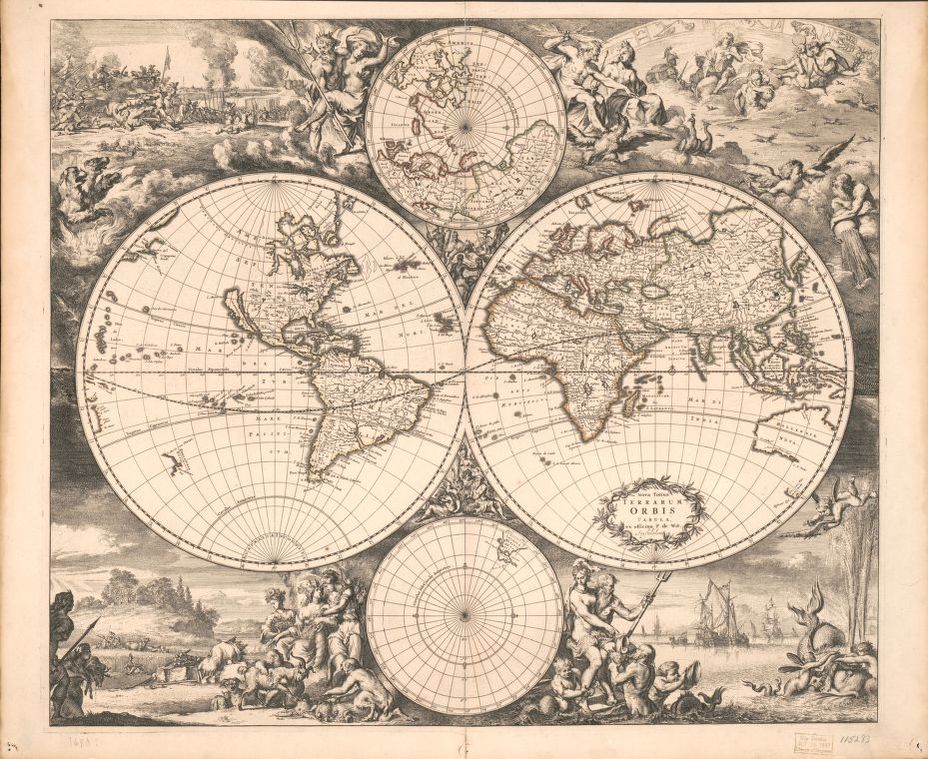

What is an Early Banjo? An Exploration of an Instrument’s Relationship to Organology and Ethnomusicology It presentation outlines the organological characteristics (how an instrument is made) of early banjos—pre-industrial gourd- and calabash-bodied instruments. It also analyzes whether organology alone can determine if an instrument is a banjo or to what extent we must consider an instrument’s provenance, usage, and cultural context. Using seven images of early banjos and the three confirmed extant instruments, we outline the organological characteristics shared across early banjos, and how those characteristics differ from known African instruments. We also discuss the known cultural context of the banjo, which was created by people of African descent in the Americas and used as accompaniment for ritual dance. Finally, we introduce a newly rediscovered instrument from a collection at the Musée des Confluences in Lyon, a watercolor at the British Museum of an instrument once held at the Leverian Museum, and a watercolor from St. Domingue, and we explore whether by using organological characteristics alone we can conclusively say that these three newly discovered sources can be called early banjos.

You can view more of the presentations from AMIS here. This is part of Banya Obbligato, a series of blog posts relating to my book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. While integrally related to Well of Souls, these posts are editorially and financially separate from the book (i.e., I’m researching, writing, and editing them myself and no one is paying me for it). So, if you want to financially support the blog or my writing and research you can do so here.

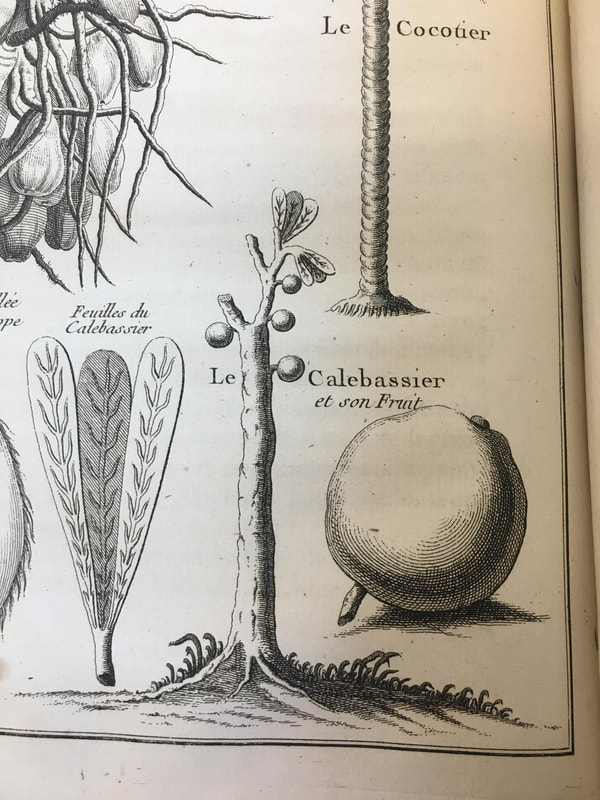

When is a calabash not a calabash? It sounds like the beginning to a botanist joke, one that I’m not sure I could find the right pun for. It is also the title of a paper by anthropolgist Sally Price, where she explores the implications of conflating calabashes and gourds on African American and Indian American art and culture. And the answer to the question actually seems to be all the time. I’ve heard calabashes called treegourds and gourds called calabash gourds. Price has an excellent table of the differences between the two fruits, but most simply put, a gourd is Lagenaria siceraria and the fruit of a vine. A calabash is Crescentia cujete, and the fruit of a tree. They are not only totally different plants, they diverge at the taxonomic classification of angiosperm, or flower plant (meaning they have a different order and family). Why does this matter?

At the beginning of my research, I was interested by the Indians seemingly close connections to other traditions that I had researched where the banjo did appear, like Junkanno (John Canoe) and Carnival in the Caribbean. In my previous blog post, I wrote about the Backstreet Cultural Museum and Mr. Sylvester Francis’s work to preserve the costumes of the Mardi Gras Indians. When I talked with my friend Tom Piazza about wanting to see the Indians as part of my research, he said that while they come out at Mardi Gras, St. Joseph’s night and the Sunday before were really the time to see them. After I saw them and continued to see references to similar outfits and processions in the Caribbean, I couldn't help thinking that this was a shared tradition, even if the specific evidence for how it was shared hasn't been well documented.

[This was originally presented at the American Folklore Society Annual Meeting in 2019 in conjunction with what I wrote about Het Koto Museum in Suriname. Mr. Francis died in 2020 and the original museum building was damaged by Hurricane Ida, but they gained a new home in July 2022. However, I’ve kept the piece in present tense as I wrote it at the time.]

|

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed