|

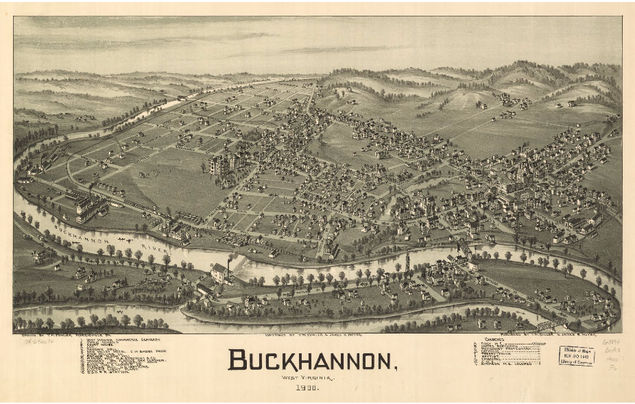

When I was working in central West Virginia, I would often see these birds-eye view maps of small towns, like Buckhannon or Elkins. I quickly realized that there was no way the artist - the maps were signed T.M Fowler - could actually have been looking down on the city. There wasn't a hill or mountain at those angles, and he surely wasn't ascending in a balloon to get the right perspective. How did he do it?

1 Comment

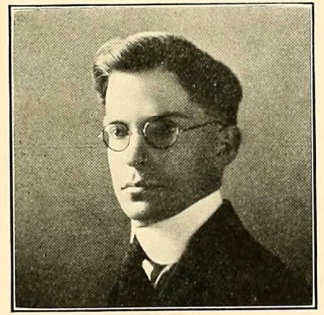

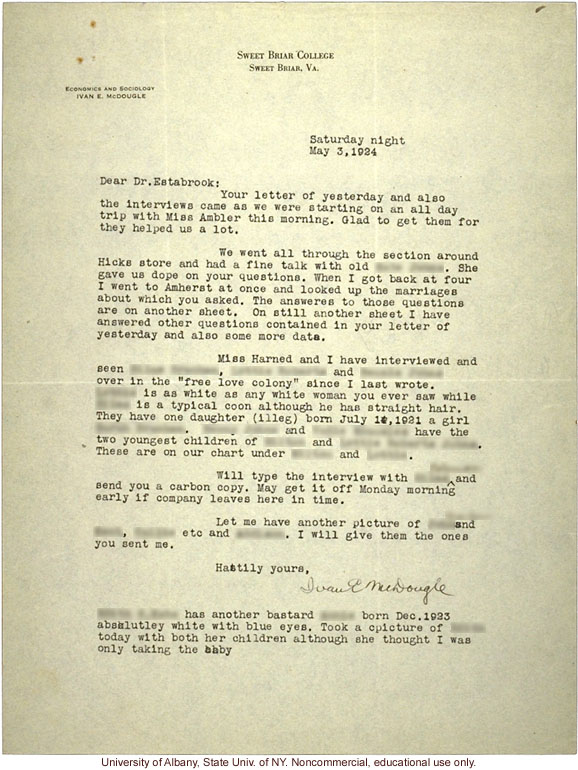

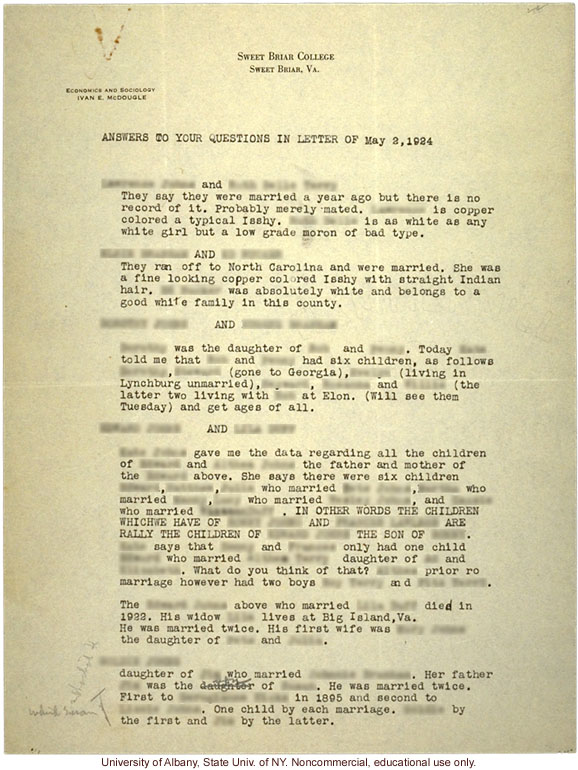

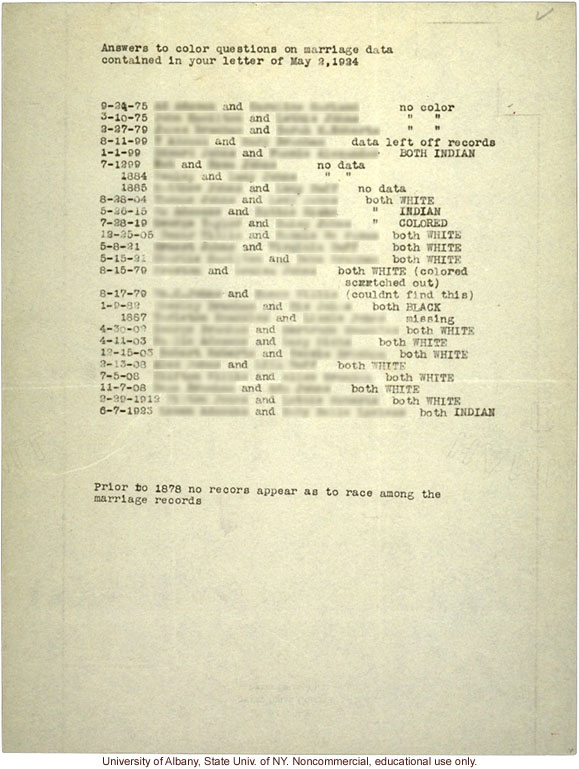

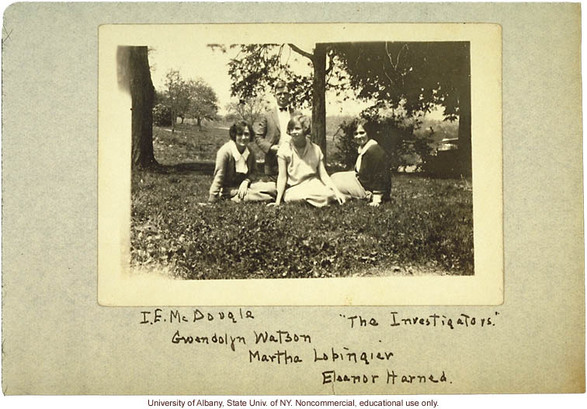

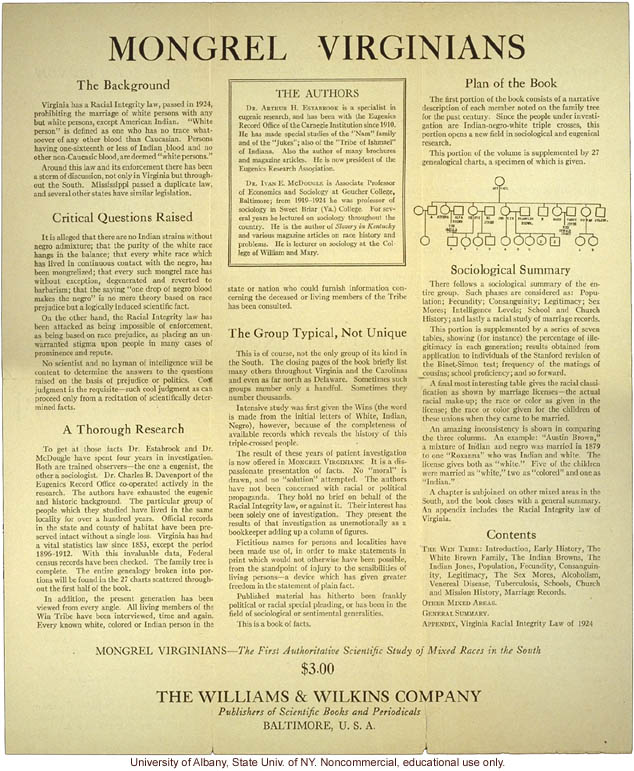

Letters between McDougle and Dr. A. H. Estabrook regarding their study in Virginia. The letters included names and places that have been redacted by SUNY Albany, who holds the original documents. McDougle grew up in the Appalachian Mountains. He was born in Tennessee to a school teacher and after attending a normal school in Kentucky, he transferred to Clark College in Massachusetts to complete his undergraduate degree. He then went on to earn both a Masters and Doctorate there. At college, Mac, as his friends called him, could not be taken from his southern roots. Friends joked in the yearbook that he was an "expert in Mooneshineology." He wrote his doctoral dissertation on slavery in Kentucky, combining both his interest in the south and race relations. After a quick stint at a boys' school in New Jersey, McDougle returned south for a job at Sweet Briar College. In 1923, McDougle paired up with Dr. Arthur H. Estabrook to investigate the mixed race people living around Sweet Briar. Estabrook was working at the Eugenics Records Office of the Carnegie Institute and had already looked into tri-racial isolate families in New York and North Carolina. At a time when immigration had just been culled, infant mortality was still a huge problem, and birth control was still illegal in many states, figuring out what traits were hereditary was vital to scientists and social workers. The middle and upper classes thought people living in tenements were dirty and stupid, but wondered if that always be a part of their lineage. Were violence, pauperism, criminality, and 'feeble-mindedness' inherited traits? Estabrook, a fellow Clark alum, now had a man on the ground to do a proper sociological study of one of these families. McDougle could interview the people and look into marriage and property records to find out as much as he could about the family. The investigators made their way to the homes of the family, called the "Browns" and the "Jones" in the study. What lay before the girls and McDougle in the hollers of the mountains was isolation and extreme poverty. The families lived in log houses and rough shacks, a few in board houses. They were farmers, relying on the finicky and grueling work of growing tobacco to make a living. Some owned their property, while others rented. There was no compulsory education, no official school. And even if there had been a public school, the one-drop rule meant that if the children were suspected of having any African ancestry, they would be forced into an inferior segregated school, if one even existed. A church operated a mission in the area, which included an elementary school, but as in many areas of the United States at the time, schooling was often overlooked for working in some capacity - whether it was in a field or in a factory. "The white folks look down on them and so do the negroes." McDougle and Estabrook reported that there lived about five-hundred members of this family in 32 square miles in south western Virginia. They called the 'tribe' the Win, representing White-Indian-Negro, yet they refrained from actually including any true information about where the people lived or what their names were. It's surprising that the researchers felt the need to protect the privacy of their subjects. This was before the days of the institutional review board and ethical approval of experiments and research studies. This was when doctors were injecting 'inferior' people with syphilis to see what would happen or removing testicles on prison inmates. It's possible that the Win tribe was what is today recognized as the Monacan tribe of Virginia. The geographic area fits (being located in Amherst County, Virginia) and some of the names that were changed remain similar to the history of the Monacans (Johns changed to Jones, Bear Mountain changed to Coon Mountain). "This study has included both mental and physical characteristics, modes of living, earning capacity, schooling, and special customs." - Mongrel Virginians, 1926 Just like census takers, McDougle and his assistants based their ideas of race on the color of people's skin. Many women he came across he described as 'white,' while those who had copper skin he considered obviously Native American, and those with dark skin were always African American. Sometimes, the authors express surprise that someone had a white parent, yet still had very dark skin. The most important characteristics always seem to be hair color, skin color, eye color, and general character. About character they wrote things like: "He is a typical Win, unintelligent and very stubborn in make up." " 'G' a boy of seven, was born with a paralysis of both legs below the hips. the physician of the State Orthopedic Clinic states that this was due to a clot of the brain." "One girl is a prostitute." A girl who gets in fights and has deformed feet, "is as fit a case for institutional care." What Dr. McDougle and Dr. Estabrook wrote has been called racist by many, and it is, but at the time, it was simply part of the eugenics movement. Using words like stupid and feeble-minded were considered appropriate determinations of intelligence. Today, we realize that the conditions of the Wins are more related to poverty than anything else. They lacked access to education. They presented physical deformities that were cause by malnutrition or lack of access to health care. They resorted to disreputable professions because it was the only way to make money. At the time, the lower-classes presented a scary view to many upper-class Americans. The 'problem' of immigration had been taken care of in 1921 with the Emergency Quota Act which was mostly geared towards keeping southern and eastern Europeans out of the United States. But what would happen when races mixed? Would degenerates breed degenerates? If the races mixed, that would eliminate the white race and bring everyone down, the eugenicists figured. McDougle and Estabrook also assume that the Wins wanted to be more white, to marry someone lighter skinned and pass for whites. The Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) allowed segregation while the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 in Virginia stated that even "one drop" of non-white blood classified a person as 'colored.' In the case of the Wins, the researchers cited their godlessness, lack of chastity, idleness, drunkenness, illness, and lack of education as proof that this intermixing has created generations of degenerates. They write that if the Racial Integrity Act "can be enforced, it will preserve racial integrity" (181). By the time their study was published, Ivan McDougle had moved on to a position at Goucher College in Baltimore, but Estabrook still worked for the Eugenics Records Office. In fact, he looked into the effect of the Carrie Buck Supreme Court Case that allowed for sterilization of the "feeble-minded." The Eugenics Movement had it's height in 1924, but it was not until after WWII and the extreme eugenics of the Nazis that the ideas associated with the movement - sterilization and isolation - were finally seen as unethical. This is a cursory overview of the topic. Check out the Eugenics Records Office, the SUNY Archive of Estabrook's Papers, and the full "Mongrel Virginians" paper for more information.

Jim Costa doesn't have an address that you can find on google maps, but tucked back in the woods next to the Greenbrier River in West Virginia, he has amassed an amazing collection of Appalachian life that's as good as any museum collection you'll see. Banjo builder Pete Ross and I went there to pick up two antique banjos made by Baltimorean William Boucher, Jr. for an upcoming exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Industry.  Jim Costa's cabin near Talcott, West Virginia. "Jimmy World," as his friend likes to call the property, has a store building that he saved from destruction, a wood shop, a blacksmith shop, and a large garage/ barn, that are pretty full to the brim with amazing antique instruments, tools, furniture, and machinery.  A box (or tape loom). This little rigid heddle loom was attached to a box that provided half of the tension of a loom. The threads that were not woven would be wrapped around the bar in the box (warp beam) and go through the little holes and slots in the tall piece (rigid heddle). On the other side of the rigid heddle, the weft passes over and under threads to form a woven band or tape. That end needs to be fastened to something (a bed post, a tree, the person weaving) to create tension that holds everything in place.  String heddles. Heddles on modern looms are usually metal, but string was common on older looms when metal was more valuable. Each string would be tied to have a loop in the middle where the long warp threads would go through. The heddles are connected to frames that lift up (or push down) so that the weft yarn can pass over and under warp yarns easily.  A reed made from actual grass reeds. They sit in between two pieces of wood that are split down the middle. The reeds stay in place with string, that was sometimes dipped in tar to keep it from unraveling. The closer the individual reeds are to each other, the denser the weaving. Some of Jim's reeds measured in at 80 dent (spaces) per inch (compare that to the 10 dent reed I have!). Of course, you can always double or triple up or skip dents in order to get the density you want. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed