|

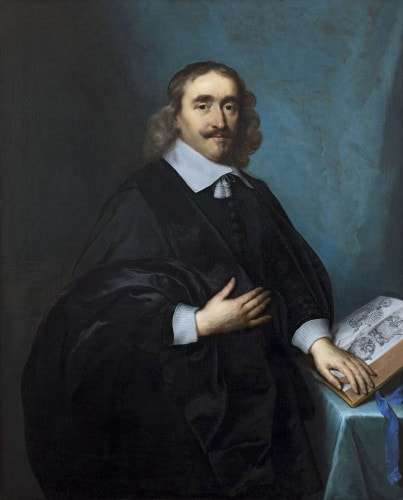

In an attempt to distract myself from devastating news about the federal mismanagement of the current covid-19 pandemic, I decided to make a linocut of a plague doctor. As if emerging from a nightmare as a cross between a crow and the grim reaper, the doctors wore long cloaks, a hood with a long beak, and eye protection. I searched for images to use for inspiration and a simple engraving print caught my eye. As I went to research more about the image, I realized it wasn’t just any plague doctor outfit, this was supposed to be an image of a real doctor, Ijsbrand van Diemerbroeck, who not only treated plague patients, but wrote a book of case studies in hopes of educating other doctors about symptoms and treatments.

0 Comments

Midwife Problems, and Solutions, part 4This is part four of a series on midwifery in Sweden and the United States. To read part one click here, part two click here, part three click here.

Midwife Problems, and Solutions, Part 3This is part three of a series on midwifery in Sweden and the United States. To read part one, click here, to read part two, click here.

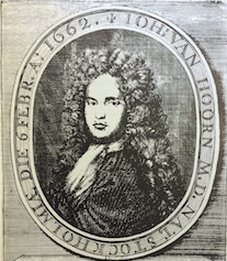

And during all this uncertainty, Johan van Hoorn was hoping someone would listen to him and his talk of jordegumman. Van Hoorn had studied medicine in the Netherlands and Paris, and had returned to Sweden to practice medicine and ended up spreading his gospel of training the midwife.

In Old English, midwife means with-woman, in Swedish jordemor (the jord comes from the Old Norse word for child or offspring) and barnmorska both mean child-mother. In Sweden at the end of the 1600s, most were untrained women known as jordegummor. Van Hoorn wanted to elevate their status, he wanted to make them barnmorskor. First, he put out the textbook called Then Swenske wäl-öfwade Jord-Gumman in 1697. In 1715, he published The Twenne Gudfruchtige I sitt kall trogne Och therföre af Gudi väl belönte Jordegummor Siphra och Pua, a textbook of questions and answers for midwives. Midwife Problems, and Solutions, Part 2This is part 2 of a series on the history of midwifery in the U.S. and Sweden. Click here to read part 1.

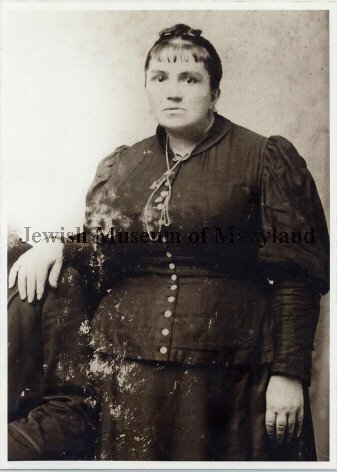

In Baltimore city, over 150 midwives delivered over 4,000 babies a year, and in every city and town in the U.S., you could find a woman delivering a baby, calling herself a midwife. But just like there were no regulations for doctors, there were no regulations for midwives. Why didn't the U.S. regulate the medical profession? And what did that mean for the health and safety of babies and mothers?

(Hey! I'm trying something new here, with a series of short, interconnected posts based on research and archives I visited in the fall of 2015, relating to Swedish midwifery and comparing it to the U.S. Let me know what you think in the contact section.) Hanna Karlen arrived in Boston on October 11, 1901 with four pieces of luggage. She was 36, traveling alone. On the ship's manifest, Karlen called herself a nurse, a statement that wasn't totally accurate.

Read the full article at OZY.com.

It is really so amazing that in modern documents like this, Frau Conti is recognized as the President of the ICM, yet there is no mention of the backdrop of what was going on in 1936 in Berlin when they held this Congress, and the terrible implications of her politics and practices.

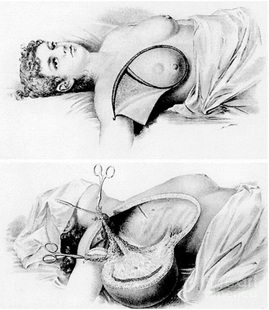

It's 1902. Two young girls are conjoined near the waist. A daring doctor decides to separate them and film it. Yup, this is a story line in Season 2 of the Knick (y'all know I love it, check out my post about Season 1 here.) If you know anything about the making of the show, it's that they do a really good job of being historically-medically accurate, thanks to their consultants at the Burns Archive. It's a story line, but it's based on a real operation done by Dr. Eugene-Louis Doyen in France on two conjoined twins named Radica and Doodica.

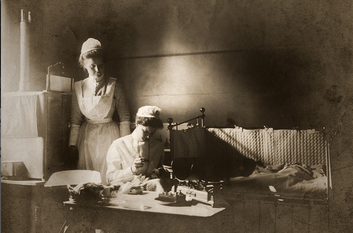

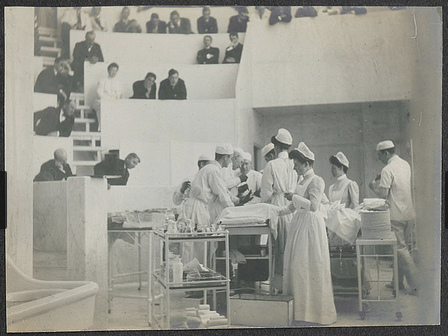

Spoilers and graphic images below...If you haven't watched The Knick on Cinemax, stop reading and start binging. (Then come back and read...)The Knick stars Clive Owen as Dr. John Thackery at the Knickerbocker hospital in 1900 New York City, and it's good TV. He is based on the Johns Hopkins Hospital surgeon William Halsted, who was by all accounts a genius, but also addicted to cocaine with a bizarre personal life. There are so many writing elements that make The Knick worth watching: characters with depth, good dialogue, a plot that moves and draws you in. And there are so many production elements that make it good: cameras that let in a lot of light so the set can have less lighting, making it feel more natural, and the extreme lengths the crew went to to make the streets of Manhattan and Brooklyn look like 1900 New York. What I like the best is how historical the show is. I spent one day last fall locked in the Chesney Medical Archives of Johns Hopkins staring at early photographs of the hospital and reading descriptions of the patient rooms and surgical amphitheaters. I came home that night and watched an episode of The Knick and my jaw dropped. The photographs came to life in amazing detail. From the Johns Hopkins Medical Archives. L: Nurse administering silver nitrate to a baby's eyes while a nursing student looks on c. 1902;

R: The surgical amphitheater c. 1903. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed