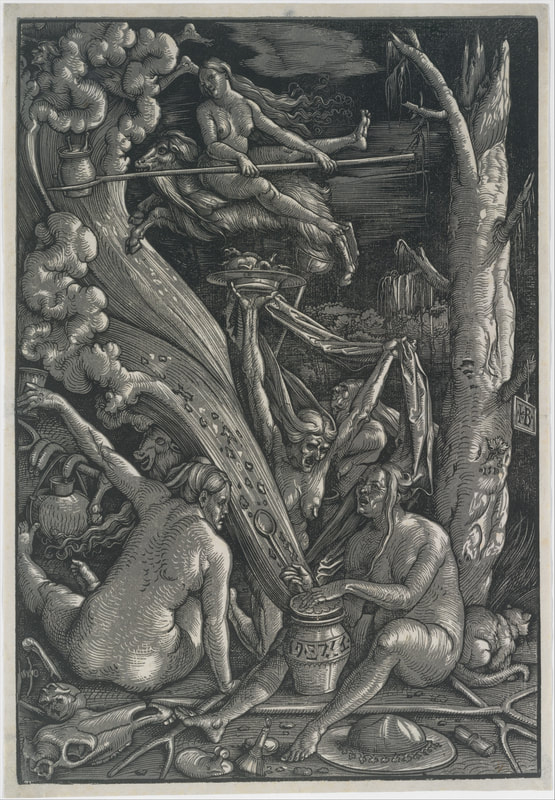

Halloween is coming, which means the spooky archive finds come to light! Let's start by exploring this amazing print from 1510 of a bunch of witches doing witchy stuff!

0 Comments

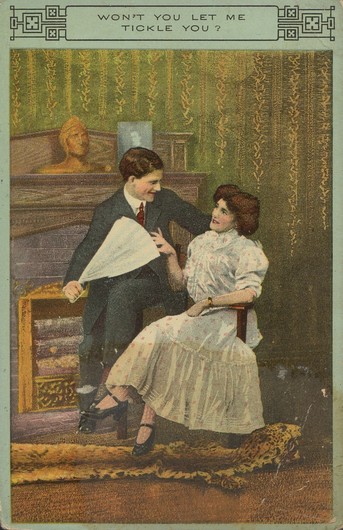

I always loved finding old greeting post-cards when I worked at the archive. What better day to share some of my favorites?Classic cupid cherubs are always a good choice for telling your valentine how much you care... But then, you can also get more original. These are two of my favorites. I couldn't decide if the one with the Dutch children is poorly translated, or if it is supposed to be wrong, as if they can't quite make their English flirting correct. And I've definitely printed copies of the tickle card. I find it such a great image of how couples had to flirt in the early 1900s.

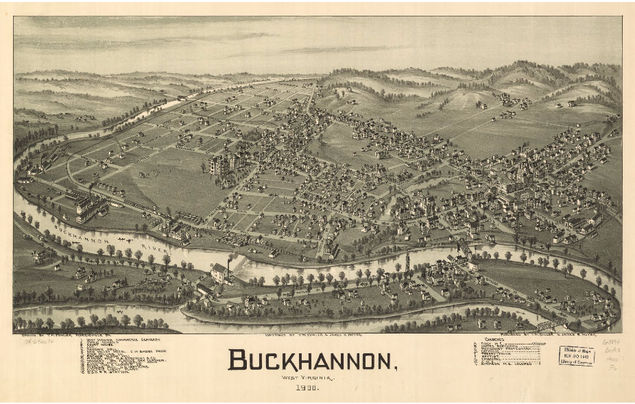

When I was working in central West Virginia, I would often see these birds-eye view maps of small towns, like Buckhannon or Elkins. I quickly realized that there was no way the artist - the maps were signed T.M Fowler - could actually have been looking down on the city. There wasn't a hill or mountain at those angles, and he surely wasn't ascending in a balloon to get the right perspective. How did he do it?

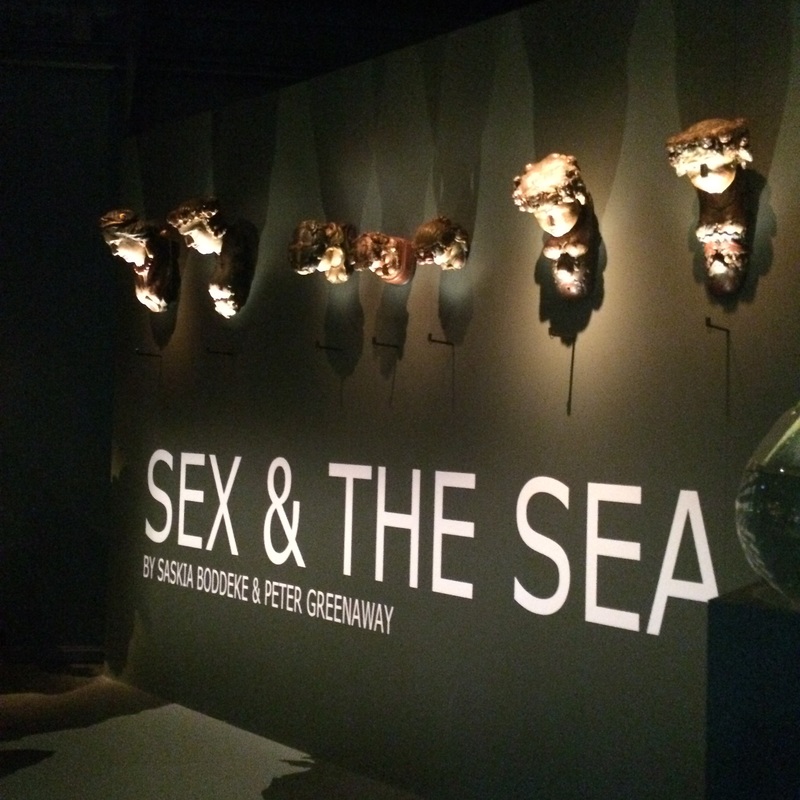

We're right in between the 2016 Republican National Convention and the Democratic National Convention, and things feel a bit divided. Maybe some images of Lady Liberty will help keep our spirits up?(This entry talks about sex in a historical and cultural way. If you don't like that, stop reading here.) The answer is no, and luckily, the Dutch and Swedes don't have as much of a problem with sex as we do in the puritan legacy of the United States. (Fun fact, while doing a presentation on sex education way back in high school, I learned that the Netherlands starts sex education in preschool. You can read more about global comparisons of that here.) The result at the Swedish Maritime Museum (Sjöhistoriska Museet) is an exhibit by multimedia artist Saskia Boddeke and film director Peter Greenaway about "identity, longing, and man's sexuality at sea."Ahh... the days of public transportation...In 1910, there were an estimated 500,000 cars in the United States for the 9.2 million people in the country. In 2015, there are over 250 million cars for an estimated 320 million people.

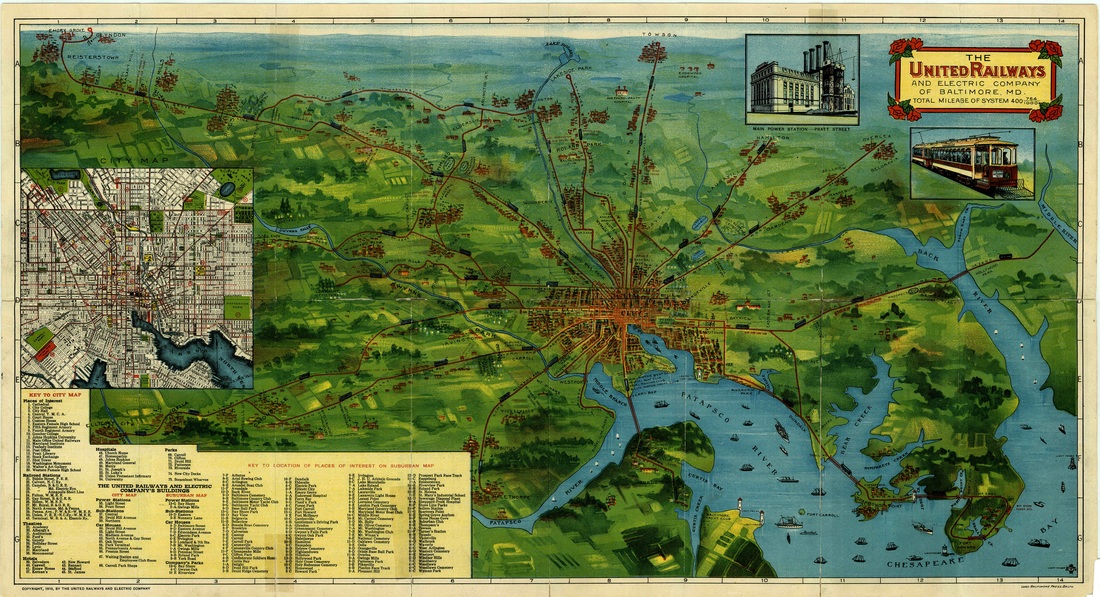

Cities were king, and public transportation was a necessity. Unlike New York and Boston, Baltimore was not developing a system of subways that would never interfere with that car traffic (and therefore never disappear). Instead, we had the trolley/ streetcar/ street railway. This map shows the trolley for the United Railways and Electric Company, which doesn't include any larger railways that had multiple stops within the city and suburbs. The closest thing we have to the streetcar today is the light-rail, which kind of follows the Halethrope Line into the city and then the Mt. Washington Line out. The light-rail then keeps going north past Lake Roland to Timonium and Cockeysville, while the old Mt. Washington Line went to Pikesville. Some close-ups are below, and click here for the full version from Johns Hopkins University Libraries. Julia Margaret Cameron's ethereal photographs were born out of a gift from her daughter and son-in-law in 1863. The camera was meant to amuse her, but she soon began to take photography as a serious pursuit. Her portraits are often close up, with a soft glow, and often with props that evoke a theatrical performance. She was making art in the style of the Pre-Raphaelites at a time when most photographers were simply doing studio portraits for profit. In these two images, from 1874 and 1875, Cameron's subjects are holding a piccolo-sized five-string banjo. The banjo is piccolo-sized (smaller than a regular banjo), fretless, and the skin head is attached with tacks, rather than tightening hardware that became more common in the 1880s and 1890s.  "Tears from the depth of some divine despair." Julia Margaret Cameron, 1875. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. "Tears from the depth of some divine despair." Julia Margaret Cameron, 1875. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The banjo is thought of as a quintessentially American instrument, but it first sprang into American pop culture in the 1840s as black-face minstrel performers took the African instrument on stage, using it to simultaneously mock and idolize African culture. Not long after the craze overtook the U.S., minstrel performers brought their music to England. The "Father of Minstrelsy" Joel Walker Sweeney first performed in London in 1843, and was so successful that he continued to perform all over England, and groups of minstrel players that were forming in the U.S. went on tour across Britain. By the 1860s, the British had their own minstrelsy tradition, with Englishmen forming their own troops and even publishing banjo instructional methods. The U.S. had a tradition of banjo playing among free and enslaved African Americans long before the minstrel show. Sweeney said he learned from slaves on his father's plantation, and while some of the traditional American banjo music of today comes from minstrel show music, there is also a tradition that comes from the African American music that predated minstrelsy or happened concurrent with the minstrel era. But no such tradition existed in England, so the banjo remained something for the stage and parlor, and Cameron's use of the banjo as a prop reflects this.

For more information on Julia Margaret Cameron, visit the Victoria and Albert Museum's website or the page for the recent exhibit of Cameron's work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For more information on the banjo in England during this time, read the article by Bob Winans and Elias Kaufman in American Music here.

|

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed