Midwife Problems, and Solutions, Part 2This is part 2 of a series on the history of midwifery in the U.S. and Sweden. Click here to read part 1.

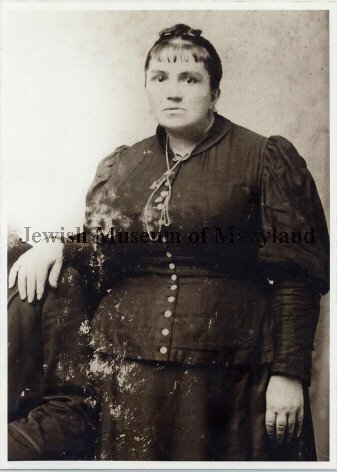

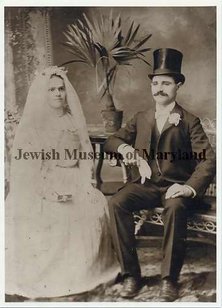

In Baltimore city, over 150 midwives delivered over 4,000 babies a year, and in every city and town in the U.S., you could find a woman delivering a baby, calling herself a midwife. But just like there were no regulations for doctors, there were no regulations for midwives. Why didn't the U.S. regulate the medical profession? And what did that mean for the health and safety of babies and mothers?

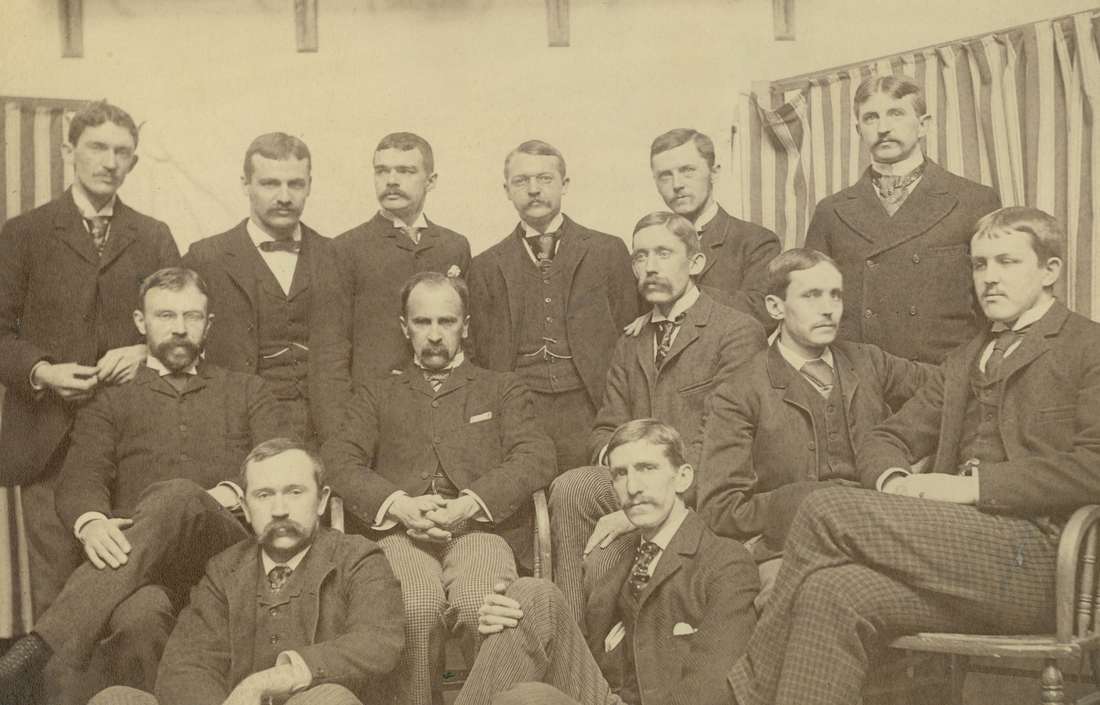

But in the middle of the 1700s, the American colonies had no medical schools or hospitals, and the medical profession itself was not professionalized in any way. Louisiana and Florida still belonged to France and Spain, respectively, and American colonies under British control were independent, mostly self-governing. While American colonies did use British law as an example, it wasn't until 1901 that England had an official policy on the training and regulation of midwives, so the colonies had no example to look towards. In what became the United States, a lack of laws and regulations meant a lack of schools and training, and left the definitions of doctor and midwife nebulous.

Regardless of what a doctor actually knew or what training he received, women in the U.S. increasingly called on him to help deliver babies. As “professionals,” they could charge more than a midwife, and were happy to do so.

Schools for midwives were nonexistent. An American midwife might not have known that washing her hands could prevent the spread of childbed fever. She might not have know that cleaning a baby’s eyes at birth could prevent blindness. She might not have known what birth complication would need more knowledge and tools than she had. She might have simply been bad at her job. With no regulation about who could practice, babies and women were those who suffered. In 1910, the United States recorded that one mother died for every 154 babies born alive, a staggering rate and almost three times higher than Sweden. So what did Sweden do right to have such a low maternal mortality rate? Next time: a brief history of Swedish midwifery.For more information about the history of midwifery in the United States, check out: Lying-In: A History of Childbirth in America; American Midwives: 1860 to the Present; Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers, and Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750-1950.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed