|

“‘Getting Up Cows,’ that’s what it’s called, ‘Getting Up Cows,” William Adams said. “An old fella played that. He was a cracker-jack old fiddler, though, I don’t believe he could beat me….” Mike Seeger hadn’t come to the neighborhood to record Adams initially, but now he wanted to hear any tune the Black fiddler could remember, even if he forgot it halfway through or couldn’t remember the name. “I forget how that goes, though, I haven’t played that since a long time ago,” the 72 year-old Adams continued before he put the bow on the fiddle’s strings and hesitantly pulled the tune from deep in his memory. In the end, it sounded like he might have just last played it a week or a year ago, not some 20-odd years earlier.

This field recording wasn’t taken in some rural hamlet or deep holler, it was less than five miles from Seeger’s home in the well-to-do suburb of Chevy Chase outside Washington, D.C. And yet in 1953, when Seeger stepped into Adams’s neighborhood of KenGar, segregation left this community so separate from the white towns and neighborhoods surrounding it, a white person might drive by without even knowing it was there.

8 Comments

I've been asked to be on a panel at SXSW - but we need community votes to make it to the event! I've been asked to be on The Banjo Project: A Digital Museum's panel at South by Southwest (SXSW), along with curator Marc Fields and the amazing musicians Dom Flemons and Tony Trishka. However, we need community votes to make it to the next round of selection!

Click here to learn more about the project, register, and vote. Read my profile of Eli Smith on OZY.

Some spooky photos and objects to get us in the Halloween mood...At this year's 19th Century Banjo Gathering (Banjo Collector's Gathering), Pete Ross and I presented on Levi Brown.

Our research uncovered that there was much more to Brown's life than just making banjos, which make sense when you know a little bit about existing Minstrel-Era banjos.

In honor of the Banjo Collector's Gathering (aka 19th Century Banjo Gathering aka Banjo Geekathon) coming to Baltimore in two weeks and my recent article about the BCG in the Old Time Herald, I thought I'd post some of the pictures from last year.These instruments are all in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

If you know the name John T. Ford at all, it's probably because he was the owner of Ford's New Theater, "which acquired such unenviable notoriety as the scene of the assassination of President Lincoln," as one of his obituaries pointed out. John Ford's life was much bigger than that one night in April 150 years ago.

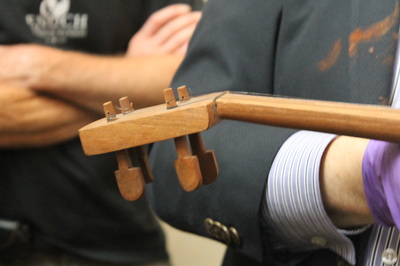

Julia Margaret Cameron's ethereal photographs were born out of a gift from her daughter and son-in-law in 1863. The camera was meant to amuse her, but she soon began to take photography as a serious pursuit. Her portraits are often close up, with a soft glow, and often with props that evoke a theatrical performance. She was making art in the style of the Pre-Raphaelites at a time when most photographers were simply doing studio portraits for profit. In these two images, from 1874 and 1875, Cameron's subjects are holding a piccolo-sized five-string banjo. The banjo is piccolo-sized (smaller than a regular banjo), fretless, and the skin head is attached with tacks, rather than tightening hardware that became more common in the 1880s and 1890s.  "Tears from the depth of some divine despair." Julia Margaret Cameron, 1875. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. "Tears from the depth of some divine despair." Julia Margaret Cameron, 1875. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The banjo is thought of as a quintessentially American instrument, but it first sprang into American pop culture in the 1840s as black-face minstrel performers took the African instrument on stage, using it to simultaneously mock and idolize African culture. Not long after the craze overtook the U.S., minstrel performers brought their music to England. The "Father of Minstrelsy" Joel Walker Sweeney first performed in London in 1843, and was so successful that he continued to perform all over England, and groups of minstrel players that were forming in the U.S. went on tour across Britain. By the 1860s, the British had their own minstrelsy tradition, with Englishmen forming their own troops and even publishing banjo instructional methods. The U.S. had a tradition of banjo playing among free and enslaved African Americans long before the minstrel show. Sweeney said he learned from slaves on his father's plantation, and while some of the traditional American banjo music of today comes from minstrel show music, there is also a tradition that comes from the African American music that predated minstrelsy or happened concurrent with the minstrel era. But no such tradition existed in England, so the banjo remained something for the stage and parlor, and Cameron's use of the banjo as a prop reflects this.

For more information on Julia Margaret Cameron, visit the Victoria and Albert Museum's website or the page for the recent exhibit of Cameron's work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For more information on the banjo in England during this time, read the article by Bob Winans and Elias Kaufman in American Music here.

|

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed