|

“‘Getting Up Cows,’ that’s what it’s called, ‘Getting Up Cows,” William Adams said. “An old fella played that. He was a cracker-jack old fiddler, though, I don’t believe he could beat me….” Mike Seeger hadn’t come to the neighborhood to record Adams initially, but now he wanted to hear any tune the Black fiddler could remember, even if he forgot it halfway through or couldn’t remember the name. “I forget how that goes, though, I haven’t played that since a long time ago,” the 72 year-old Adams continued before he put the bow on the fiddle’s strings and hesitantly pulled the tune from deep in his memory. In the end, it sounded like he might have just last played it a week or a year ago, not some 20-odd years earlier.

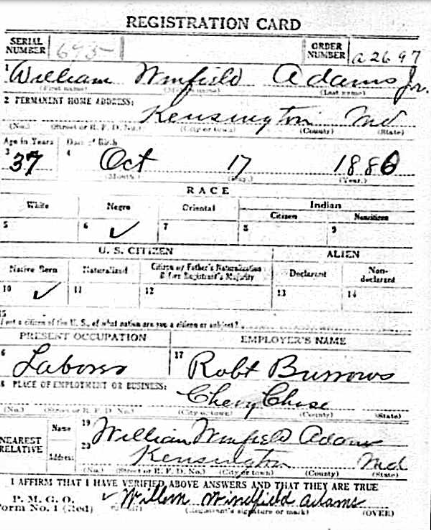

This field recording wasn’t taken in some rural hamlet or deep holler, it was less than five miles from Seeger’s home in the well-to-do suburb of Chevy Chase outside Washington, D.C. And yet in 1953, when Seeger stepped into Adams’s neighborhood of KenGar, segregation left this community so separate from the white towns and neighborhoods surrounding it, a white person might drive by without even knowing it was there. Ninety-seven lots on five streets make up the KenGar subdivision, tucked away between the Victorian garden suburbs of Kensington and Garrett Park. Bordered on the south by the B&O Railroad tracks, the north by woods, the west by Rock Creek, and the east by the streetcar tracks, only one road led in and out of the neighborhood. In the early years of land sale in KenGar, the Lee African Methodist Episcol Church bought lots and sold them to African Americans. Adams’s father, William Winfield Adams, Sr., bought two lots around 1912 from the church. He was born in Maryland around 1847, when slavery was still legal, although he may have been born free [FN1]. More African Americans, some moving from Black communities in nearby Rockville or Sandy Spring, bought land and built houses in the neighborhood and it quickly became a Black enclave in a predominantly white town. Shortly after his father moved to KenGar, William W. Adams, Jr. bought a lot and moved with his wife and children to a home on what would become known as Hampden street.

The Adams family went to church at the newly-formed First Baptist Church of Ken-Gar, just across the street. They’d been founding members since the church was formed in the neighbor Mrs. Davis’s living room. Other families attended worship at the Lee AME Church, just around the corner. They left the neighborhood for work in the surrounding white homes and businesses. Adams worked as a laborer, like most men in the neighborhood, his wife Florence worked as domestic, like most women in the neighborhood. Some of the men worked as caddies at the nearby golf clubs in Chevy Chase. The gateway from KenGar to Kensington on Bonnycastle street, the road that left the neighborhood to the outside, was intentional in so many ways. Black residents of KenGar could not play at the golf club where they worked, they could not sit wherever they wanted on the streetcar on their way down Connecticut Avenue, and they could not buy the houses they passed, houses with running water and indoor toilets, because of they would be denied home loans or covenants disallowed home sales to Blacks. Segregation laws, policies, and practices kept the gate closed.

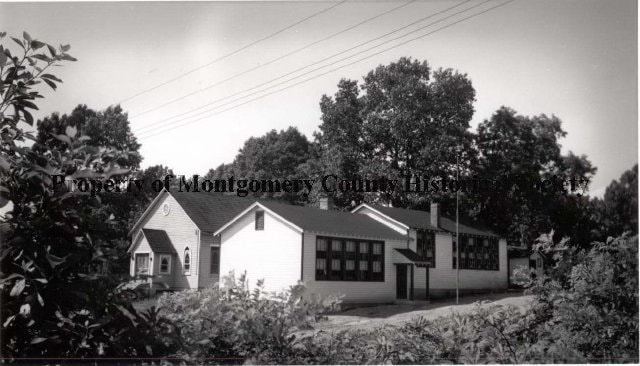

For KenGar’s school, the community raised $500, while Rosenwald gave $200, and the county paid the remaining $2,300 to build a one-room schoolhouse next to the AME Church. The Baltimore Afro-American saw the inequity immediately with a headline that read, “Six White Schools Get $180,000 While Eleven Colored Get Only $36,573.” The white schools would be brick, the Black schools would be wooden, the difference in cost and quality stark. The white students had an elementary, middle, and high school nearby, the Black students could attend the KenGar school until middle school, and then have to go to Lincoln High School in Rockville. In 1937, the Kensington Community Club, a group of white women, took up donations to build an addition on the school, but separate was clearly still not equal. In the center of Kensington, the Town Hall hosted dances, lectures, and political meetings that excluded Black residents, unless they were providing entertainment or serving food or drink. In 1915, pianist Leonard Meads and his drummer Bluejay came from Rockville to provide music for a dance. William Adams and his band played for white dances around the area, with versions of Irish jigs and dance tunes in his repertoire. But hiring Black musicians didn’t keep the white Kensington residents from lampooning the residents of KenGar. In 1912, the Town Hall hosted the Kensington Athletic Club’s annual evening of entertainment featuring the KenGar Minstrels. The evening was not made up of musical acts from KenGar, but rather white Kensington residents performing a “Darktown song and dance.” Although the Blackface Minstrelsy music craze had started to fade by the 1870s, the practice of entertainers painting their faces black and imitating African Americans continued well into the 20th century. The one road that led out from KenGar to Kensington also kept unwanted people out of the community. Lynchings and threats against Black lives were real. Neighbors knew each other, and could see who was coming and who was going, keeping a keen eye on people who weren’t supposed to be there. Mike Seeger had made his way from his family’s home in Chevy Chase to KenGar in hopes of finding a banjo player. Like the old street car, he went north just a few miles on Connecticut Avenue to Kensington and then into KenGar, looking for a man he knew as Sam. In 1952, the banjo had taken over Seeger’s mind. His older half-brother Pete was already becoming well-known in the folk revival scene as a banjo player and with little interest in college or anything else, banjo music began taking over Mike’s life. His parents had bought him and his sister an S.S. Stewart banjo, and he’d lock himself in his room trying to learn tunes and technique. His ethnomusicologist father and composer mother invited musicians like Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter to their home, his father had taken him to the Old Fiddler’s Convention in Galax, Virginia, and he knew about recording unknown musicians through his parents work and that of their friends like the Lomaxes. That summer, he saw Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys at a country music park in Mt. Airy, Maryland and met Dick Spottswood, a young record collector who turned him on to 78s of old-time country music. He was obsessed with learning everything he could about old-time music and 5-string banjo playing, and doing it authentically. Had this obsession not happened in that year, he may have never met and recorded William Adams.

Not much, he told Seeger, he hadn’t played for about twenty-five years. He used to play with a stringband. Seeger, wanting to absorb as much banjo knowledge as possible, handed the man his instrument. The man rounded his right hand over and began to play, striking down on the strings and finding the melody with his left hand. His playing was solid, but out of practice, thought Seeger. He played a few tunes before Seeger asked him if he couldn’t come record his playing. The only recording Seeger had done himself was a tape of Elizabeth Cotten, an outstanding guitar player who happened to also work for the Seeger family. He’d never taken recording equipment out into the field. Sure, the man said. He told Seeger his name was Sam, and that he could find him in KenGar.

At this same time, the homes in KenGar still had no connection to municipal sewer and water lines, and half of the neighborhood was still unpaved. Landlords refused to install indoor bathrooms. The neighborhood had no sidewalks, no street lights, no storm drains. Residents complained to the county government, but change was slow. The children still went to the segregated KenGar school and residents still left the neighborhood for work. After World War II, Blacks arrived in the Washington, D.C. area as part of the Second Great Migration, and found a home in KenGar, where churches and residents welcomed them. Mike Seeger lugged his recording equipment, a reel-to-reel recorder in an oak box, to KenGar, hoping to see Sam again. Even with all the development happening around KenGar, Seeger still felt the neighborhood felt like any rural town he’d visited across the country. He didn’t know Sam’s last name, and he began asking around, perhaps thinking that small-town feel would lead him to Sam. No one would help him. He thought they might be protecting Sam, but from what he didn’t really know. At 19 and as a novice folklorist, he didn’t know how to get around that. Sam had mentioned he used to play with other musicians, and someone pointed Seeger towards William Adams’s home. Seeger misheard and thought the fiddler’s name was Will Adam [FN2]. The errors Seeger made highlight his novice. He thought Adams looked about 60, when really he was 72, and he thought Adams’s teenage daughter was hanging around, when it was more likely a granddaughter, adopted daughter, or other relative [FN3]. He seemed to be so focused on getting tunes from Adams that he didn’t ask him about the rest of his life. Adams didn’t own a fiddle any longer, and like Sam, he said he hadn’t played in twenty-five years. But Seeger handed over his own fiddle and asked Adams to play, and Adams did. He played full tunes he could remember, parts of tunes that he said he couldn’t remember so well anymore, and made comments here and there about the tunes. Before he played "I Went Down to the Racoon's Den to Get a Bag of Corn," he chuckled and added the lyrics, "Racoons set the dogs on me, and the possum blowed the horn." [FN4]

Mike Seeger would later regret that he didn’t look harder for Sam and get a recording of his banjo playing and that he didn’t spend more time with William Adams.

The readily available print sources for what happened in KenGar through the years are sparse. Most of the reporting in this post is from an unpublished history of KenGar by Munro P. Meyersburg from the Kensington Historical Society, a few other histories of Kensington, and government records. Newspaper articles about KenGar cover when a school is being built or finally desegregated in 1955, or when in the 1970s, residents are still complaining about the lack of municipal resources like storm drains. White newspapers definitely didn’t cover marriages, deaths, or other community news. Residents saw each other all the time and gathered regularly for church and community events. So when I searched William Adams in the archive of The Washington Post, I didn’t expect to get any results. Instead, I got a tragedy. On Saturday, March 14, 1953, Preston Lewis and Kathleen Albert were playing outside their house on Hampden Street in KenGar. They lived just a few houses down from Adams. He was driving and hit them both. Whether it was getting dark or the two ran in front of his car and he didn’t see them, the newspaper doesn’t say. Preston and Kathleen were taken to Suburban hospital, where Preston, age 5, later died. Kathleen had broken her ankle. Adams received a two year suspended sentence for manslaughter. The two newspaper stories are just a paragraph each. Is there more to the story? Absolutely. It is a story that can’t be heard on a recording, can’t be recounted by someone who only met Adams a few times, can’t be revealed by words on a page. It is the story of a man recognized for one of his talents by luck, of a life well-known by friends and family, and of a tight-knit community regularly subjected to tragedy and injustice. FN1: : 1850 Census and 1860 Census records match someone who could be Adams Sr., who was free by 1850 in Caroline County. This freedom may have been what enabled him to accumulate the wealth needed to buy property. FN2: "Will Adam" has to be William Adams, since no other Adam/ Adams lived in KenGar] FN3: The 1940 shows the only child of William and Florence Adams as Delia (or Delie), and at age 17, she would have been an adult by the time Seeger visited. FN4: In addition to 15 unnamed tracks, the named tracks are:

Resources:

8 Comments

6/17/2020 01:36:20 pm

Thank you so much for making this information available! Do we know when Will Adams died? Mike gave me these recordings a long time ago, but I didn't know any of the back story at all, other than that Will Adams was black.

Reply

mary knight

2/14/2021 03:02:40 pm

Suzy, I live in KenGar. I will ask my friend whose family has lived there for generations. If I do learn anything about Will Adams and maybe Sam (banjo), I'll reply here.

Reply

mary knight

2/14/2021 02:30:46 pm

Wow! Just wow! I have lived in KenGar for about 20 years. I never heard these stories. I am also a fiddle player and a former co-editor of the SF Folknik, when Pete Seeger submitted to us his recipe for strawberry shortcake. I know two KenGar historians and will share this with them and would like to add the link to the KenGar history site and share on our community listserv. I hope I can access Will Adams' music and listen and learn some of the tunes!

Reply

7/29/2021 01:03:33 pm

Has anyone been able to make contact with any of Will Adams' descendants?

Reply

mary knight

7/29/2021 01:26:52 pm

Please contact me at [email protected]. Also, Jake Blount has studied and revived his music: JakeBlount.com

David (Tim) Zwerdling

2/15/2021 09:09:14 pm

wonderful! the history, the connectiion between KenGar and the Seeger family, hearing Will Adams talk, and his fiddle playing. Sad history of segregation, but impressively solid community. Pleased to hear Julius Rosenwald helped fund the school. In Reform Judaism, a key principle is Tikkun Okam, repair the world....

Reply

11/10/2022 10:32:40 am

I just discovered this great article! Thank you so much for this, it fills in some blanks I've been missing about Mr. Adams' life, and about the Ken-Gar neighborhood, not far from where I used to live.

Reply

David Brown

7/16/2023 01:36:00 am

I just discovered this page - what an amazing piece of research - thanks for posting. All I had known previously was the info in the liner notes of "Close to Home" - wonderful to hear the whole story.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed