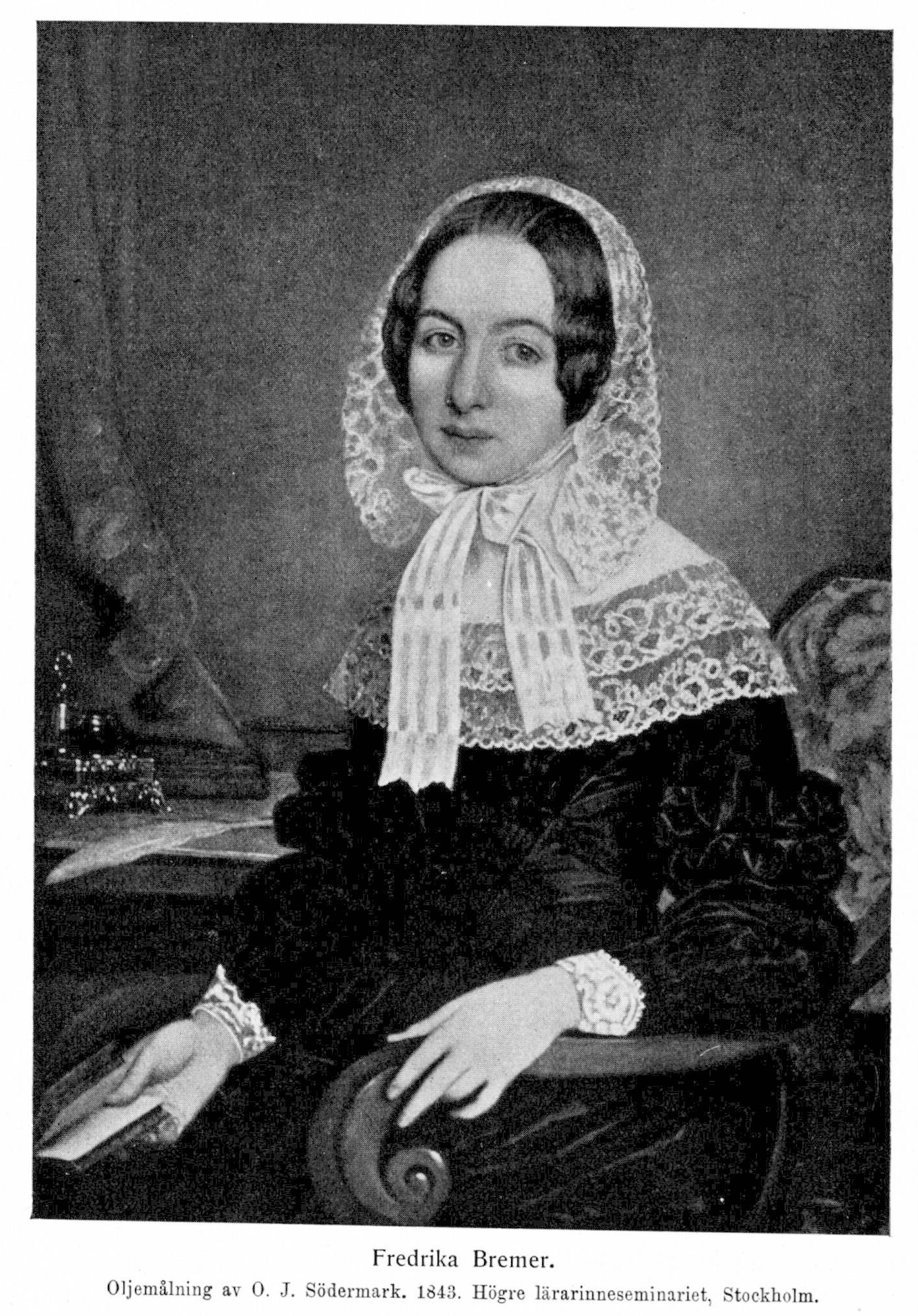

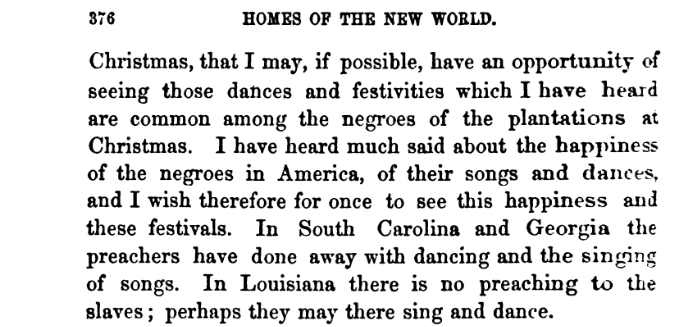

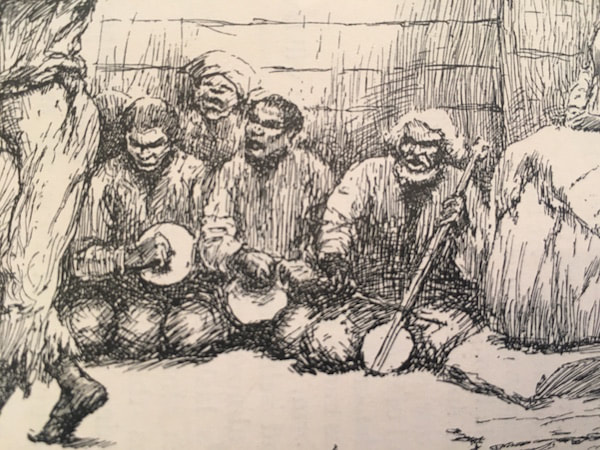

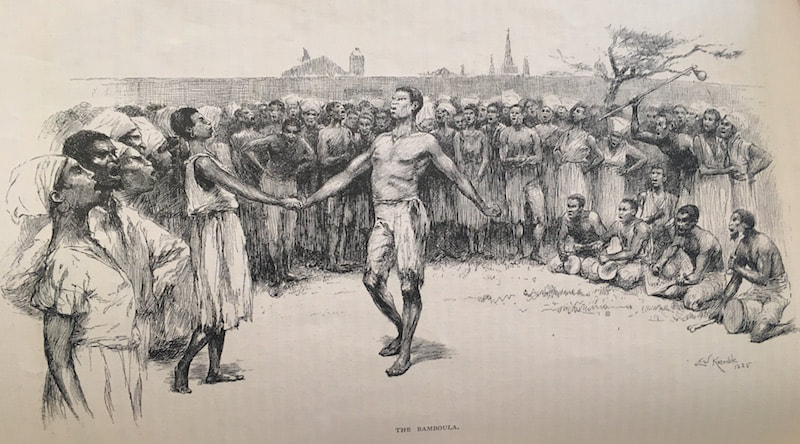

Perhaps because Bremer's book started as letters from America back to her sister, she documents many things that she finds fascinating and different about the United States and other places she visits. Epstein found Homes of the New World: Impressions of America interesting because Bremer presents accounts of music and dance before the Civil War. In fact, Bremer is longing to see the songs, dances, and festivals of American Blacks. But by 1851, she isn't seeing what she's heard. Epstein quotes her: "I have now traveled in search of these negro festivities from one end of the slave states to the other, without having been lucky enough to meet with, to see, nay, nor even to hear of one such occasion. I believe, nevertheless, that they do occur here and there on the plantations." Bremer was a well-read woman, and by the mid 1850s, many Europeans understood certain concepts of African American culture. In her case, I would have really liked to know what they were based on. She could have read John Gabriel Stedman's best-selling memoir, which included actual descriptions of dance and music from the enslaved in Suriname. Or, she could have attended an extremely popular Blackface Minstrel show, which purported to show realities of the lives of the enslaved. Although the origin of the songs and tunes the white men in blackened faces performed cannot be well substantiated, they did rely heavily on stereotypes of "Southern" and "Black" life. These were stereotypes, that as enlightened as Bremer was, she also couldn't seem to get past. Although she thought integrated schools were great, met with abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, and ended up believing that the 'happy slave' trope often seen in Blackface Minstrel shows was a lie, "Her comments often revealed paternalist racism of the time period," Professor Sirpa Salenius writes in “The Antebellum South in Frederika Bremer’s Travel Letters." Above and below: Late 19th century illustrations done by E.W. Kemble for George Washington Cable's reminiscences of New Orleans. Born in 1844, Cable never witnessed any of the Place Congo/ Congo Square dances himself, but relied on earlier accounts, sometimes ones that didn't even come from New Orleans. Kemble, meanwhile, based his images on Cable's writing. Images courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection. Bremer doesn't witness any dances, music, or festivities in New Orleans like she had hoped. When she finally does see music and dance in Haiti, her descriptions reveal those "dominant racist notions" of the time. According to Professor Salenius, Bremer presented the enslaved as "looking for ways to express their African identity and subculture," which she did not frown upon in principle. However, the language she uses to describe these dances isn't different from most travelogues written by white Europeans-- i.e. filled with racist portrayals that classify the actions as wild, lascivious, and athletic, and unable to see past those stereotypes to understand the dance and music more fully. As I continue researching and writing Well of Souls, I imagine I'll spend more time with Bremer's impressions of America.

1 Comment

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed