We walked down a quiet street in central Paramaribo and I checked the map on my phone to make sure we were in the right place. We arrived at a well-kept but unassuming green and white house, a house that has become home to the tradition of Koto Misis. Here, Christine Van Russel-Henar is preserving and documenting the clothing of Afro-Surinamese women, and preserving a tradition and a culture. One of the first things I saw when I entered was a photo of Van Russel-Henar’s mother, grandmother, and great-aunt in koto outfits from around the 1920s. Although the photo is black and white, you can still see the patterns, and the mannequins that fill the room let you see the rich and bold colors of the kotos. They wear large skirts, structured jackets, and elaborately-tied headscarves. The women who bear this tradition are called Koto Misis, and the koto outfits originate in the ritual dramas like the banya prei. The banya is a ritual play that combines song, dance, and role-playing in a religious ceremony to establish contact with ancestors, spirits, and gods. This developed into the du, which included secular or non-religious plays.

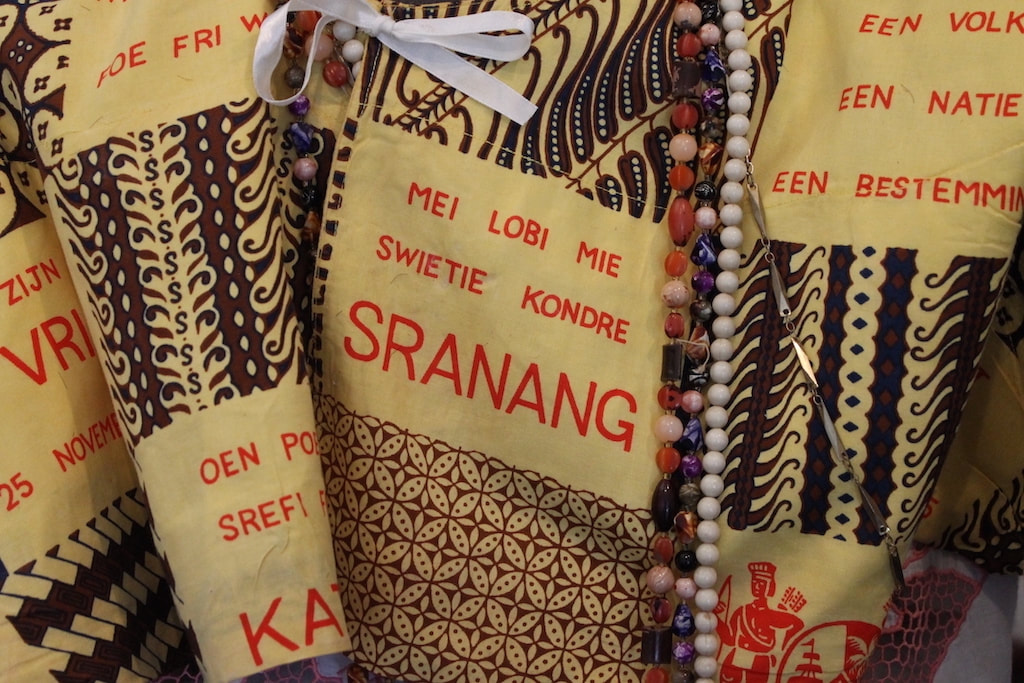

In the banya, handkerchiefs are representative of events or proverbs so that dancers and actors could communicate without words during the play, and the design would determine the meaning, yet the design and name are usually arbitrary [3,4]. The female lead is called Afrankeri. She is the storyteller who explains and defends high morals to the observers, and could be distinguished by her costume [5]. In the Surinamese English-based Creole Sranan Tongo, afrankeri means to display or flaunt, and the Afrankeri displays her most beautiful outfit [6]. In Gerrit Schouten’s dioramas, she stands centrally in the scene with her hands clasped but is not engaged in the dance. This outfit later developed into the Koto Misi costume [7]. The banyas were also a form of resistance: the white enslavers did not understand the deeper meanings of the plays, and the plays made commentaries about slavery and plantation life [8]. One song had the lyrics “Let’s run away o, Brother,” and during a banya play in 1862, every enslaved person from one plantation actually did take their own freedom [9]. Later in the 19th century, the groups that put on plays became known as Du societies. These dances and societies didn’t have just one purpose. They served social, cultural, ritual or religious, and mutual-aid functions, in the last of which they payed for funerals of other members [10]. When I visited Christine van Russel-Henar and Het Koto Museum in the summer of 2018, she explained that before emancipation in 1863, free women of color wore the outfits as an expression of pride, and resistance. The colony forbid enslaved women from wearing jewelry and shoes, and they didn’t have the opportunity to buy large pieces of expensive fabric. The high point of the Koto Misi costume came after emancipation, when Afro-Surinamese women were finally able to express themselves freely. The headscarves became a special tool of communication between women. Using mashed cassava and water as starch, Afro-Surinamese women shaped fabric into angisa (headscarves), folded at the back of the head to create a kind of hat. The odo (pattern names) were sayings like “The garbage truck collects garbage but not shame” and “I am a grown woman in my own house, I can do as I please,” while the folding could say, “Hold your tongue,” “Wait for me at the corner” or “Let them talk.” However, by the mid-20th century, younger women were less interested in carrying on the tradition of the banya, the Koto Misi outfit, and the messages carried on fabrics and folding. Van Russel-Henar’s mother, Ilse Henar-Hewitt, became obsessed with the angisa, and wrote the first book about Koto Misis in 1987. In her book Angisa Tori, Van Russel-Henar writes, “My mother had laid the foundation and now I could start my own research with Sisis (Slijngard, a tradition bearer) as my teacher and great friend" [11]. Van Russel-Henar compiled a database of [head kerchiefs], taking photos and writing down every detail she could; talked with older women who remembered the tradition; and then started collecting the angisa and fabrics. In the late 1990s, Van Russel-Henar revived public Du performances and showcased koto outfits in fashion shows in Suriname and the Netherlands. She opened the museum in 2009 as a natural extension of her work. She felt it was the next step after publishing her book on the kotos, and felt that people needed to see her personal collection, which includes 200 headscarves alone. She sees that many people who visit have a spiritual experience in the museum, they are getting to know their culture, and because of that, they won’t lose it, she adds. She likes the idea that the angisa are sold in the market and tourist shops around Paramaribo. Today, some women design new kotos for holidays like Suriname’s independence and Koto Keti, or the Breaking of Chains/ Emancipation Day. When we walked around the market looking for fabrics, a seller told me I couldn’t possibly want to buy the fabric I had selected, since it was last year’s pattern. Women also wear the outfits on feast days, celebrations, and school events. Organizations teach classes in folding, but these classes might not exist without Van Russel-Henar’s research. She says, “Now that the museum is here, we see much more pride in the history.” This was originally presented at the American Folklore Society Annual Meeting in 2019. All photos are ©Kristina Gaddy and can be used with permission. [1]Baron Albert Von Sack, Narrative of a Voyage to Surinam of a Residence there during 1805, 1806, and 1807 and of the Author’s Return to Europe by the way of North America, G. And W. Nicol: London, 1810. [2] H.C. Focke, “De Surinamische Negermuzijk” in West-Indië: bijdragen tot de bevordering van de kennis der Nederlandsch West-Indische koloniën vol. 2, ed. A.C. Kruseman (Haarlem: A.C. Kruseman, 1858), 95[3] G.M. Martinus-Guda, "Banya: A Surinamese Slave Play that Survived,"African Re-Genesis: Confronting Social Issues in the Diaspora, edited by Jay B Haviser, Kevin C MacDonald.[4] Herskovitz, 7. [5] C. Medendorp, “History in a Diorama,” Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum vol. 54, no. 3 (2006), 327 [6] Clazien Medendorp, Kijkkasten uit Suriname: De Diorama’s van Gerrit Schouten (Amsterdam: KIT Publishers en Rijksmuseum, 2008) , 74 [7] Medendorp, "History in a Diorama," 327[8] Medendorp, "History in a Diorama," 328. [9] Medendorp, Kijkkasten, 74. [10] Trudi Guda, “Banya: a Surviving Surinamese Slave Play,” in A History of Literature in the Caribbean Volume 2: English- and Dutch-Speaking Regions, ed. A. James Arnold (Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2001), 615. [11] Christine Van Russel-Henar, Angisa Tori de geheimtaal van Suriname's hoofddoeken, Paramaribo : Stichting Fu Memre Wi Afo, 2008. This is part of Banya Obbligato, a series of blog posts relating to my book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. While integrally related to Well of Souls, these posts are editorially and financially separate from the book (i.e., I’m researching, writing, and editing them myself and no one is paying me for it). So, if you want to financially support the blog or my writing and research you can do so here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed