|

“Wait, is his name Charles or is the name of the king King Charles?” someone asked me after reading a draft of Well of Souls. In Albany, New York, the most well-remembered King of the African American Pinkster celebration was Charles, but Albany wasn’t the only place that had Pinkster celebrations and Charles wasn’t the only king. In Antiquities of Long Island from 1874, Gabriel Furman writes that although at first Pinkster, “the day of Pentecost,” was celebrated by Black and white New Yorkers, it “eventually became entirely left to the former,” and was never as popular on Long Island as it was in Albany. On the hill where “the Capitol now strands,” booths were set up and Black people came from near and far to celebrate. The dance as he remembers it was called the “Toto dance,” which was danced to “a hollow log, with a skin of parchment stretched over one end, the other being left open, on which they beat with a stick, making a rough, discordant sound,” a drum Furman calls the “banjo drum.” [1]

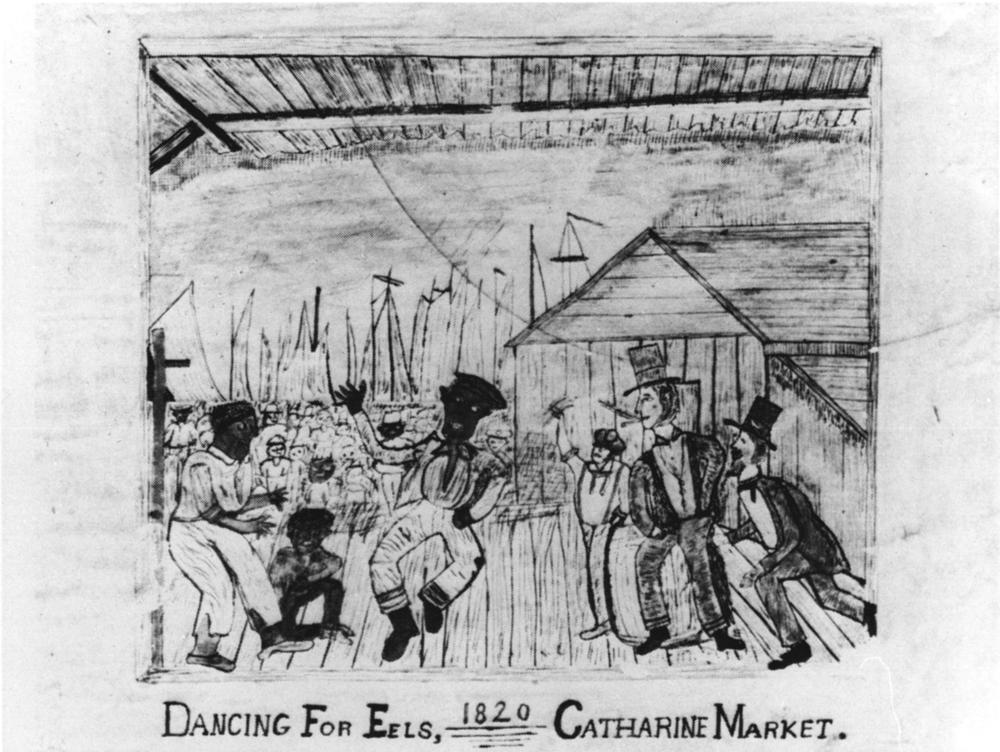

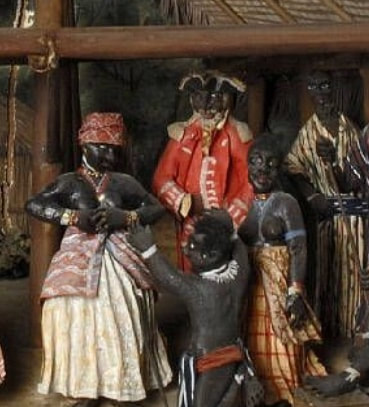

Many of the accounts of Pinkster (including fictionalized accounts in novels like James Fenimore Cooper’s Satanstoe) show up not only long after the festivity was no longer a regular occurence, but after the end of slavery in New York. In addition to describing Pinkster in Albany, Furman writes that Pinkster was celebrated on Long Island, too, and that even in 1874 “especially on the west end of this island, it is still much of a holiday.” On the other side of the island in Brooklyn, “men, women and children, sometimes as many as two hundred” came to the market to celebrate Pinkster. “They danced for eels around the market; they sang; "tooted" on fish horn; played practical jokes on one another,” wrote Henry Reed Stiles in 1869. People also got drunk and arrested for disorderly conduct, apparently, but Stiles reports that they were let off with a fine since Pinkster only happened once a year. [5] Across the river in Manhattan, Pinkster in the late 1790s was a “universal observance” and “boys and negroes might be seen all day standing in the market place, laughing, joking, and cracking eggs. In the afternoon, the grown up apprentices and servant girls, used to dance on the green in Bayard's farm in the Bowery,” according to an 1846 reminiscence. [6] In 1838, The New-York Mirror reported that two of the Pinkster celebrants were Billy the fiddler, who stood “four feet nothing in his stocking feet, and [was] deeply versed in the mysteries of catgutt” and Pot-pie Palmer “a light-hearted, shirtless vagabond, who, during the prevalence of the yellow-fever, trundled the dead to their graves, singing ‘Yankee-doodle,’ and ‘Hail, Columbia!’” [7] During the excavation of the African Burial Ground in New York, one man was found wearing a red military coat, which has led people to speculate that he was a Pinkster King. And while we suspect that other Pinkster celebrations had their own kings, King Charles is the only king found in historical sources. (I default to the idea that there are very few contemporaneous sources that discuss Pinkster, which was often because white people with the means to document Black customs didn’t care enough to do so. And the later sources, which impart a sense of nostalgia for pre-slavery times, all seem to draw on each other.) However, in an 1894 article about Pinkster by historian Alice Morse Earle, she notes that around the same time as Pinkster (May or early June), Black residents throughout New England held an “Election Day” where a “Black Governor” was elected. In Windsor, Connecticut, the master of ceremonies in 1820 was a man named “General Ti,” enslaved to “Calt. Ellsworth.” [8] Like Calenda/ Kalinda dances elsewhere, similar traditions of celebrations and electing a king or master of ceremonies may have had different names but essentially served the same purpose: to carry religious and spiritual traditions forward in new ways, adapted to and integrated with the culture of white European Americans in power. Read more about Pinkster and African American history in New York:

Notes [1] Gabriel Furman, Antiquities of Long Island, 235-239. [2] Furman, Antiquities, 323-327. [3] Dewulf, The Pinkster King, 60. [4] Dewulf, "Rediscovering Pinkster," 17. [5] Henry Stiles Reed. A History of the City of Brooklyn, Volume 2. 1869 39-40. [6] John F Watson. Annals and occurrences of New York city and state , in the olden time : being a collection of memoirs, anecdotes, and incidents concerning the city, county, and inhabitants, from the days of the founders. Philadelphia : H.F. Anners, 1846, 178. [7] The New - York Mirror: a Weekly Gazette of Literature and the Fine Arts 1823...Apr 14, 1838; 15, 42; American Periodicals Series Online pg. 330 [8] Alice Morse Earle. “Pinkster Day. “ Outlook (1893-1924); Apr 28, 1894; 49, 17; American Periodicals Series Online pg. 743-744. This is part of Banya Obbligato, a series of blog posts relating to my book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. While integrally related to Well of Souls, these posts are editorially and financially separate from the book (i.e., I’m researching, writing, and editing them myself and no one is paying me for it). So, if you want to financially support the blog or my writing and research you can do so here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed