|

I spent February at the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis on a William Reese Company Fellowship, looking at the papers of Captain John Gabriel Stedman and investigating the banjo's early history in Suriname and the Caribbean.

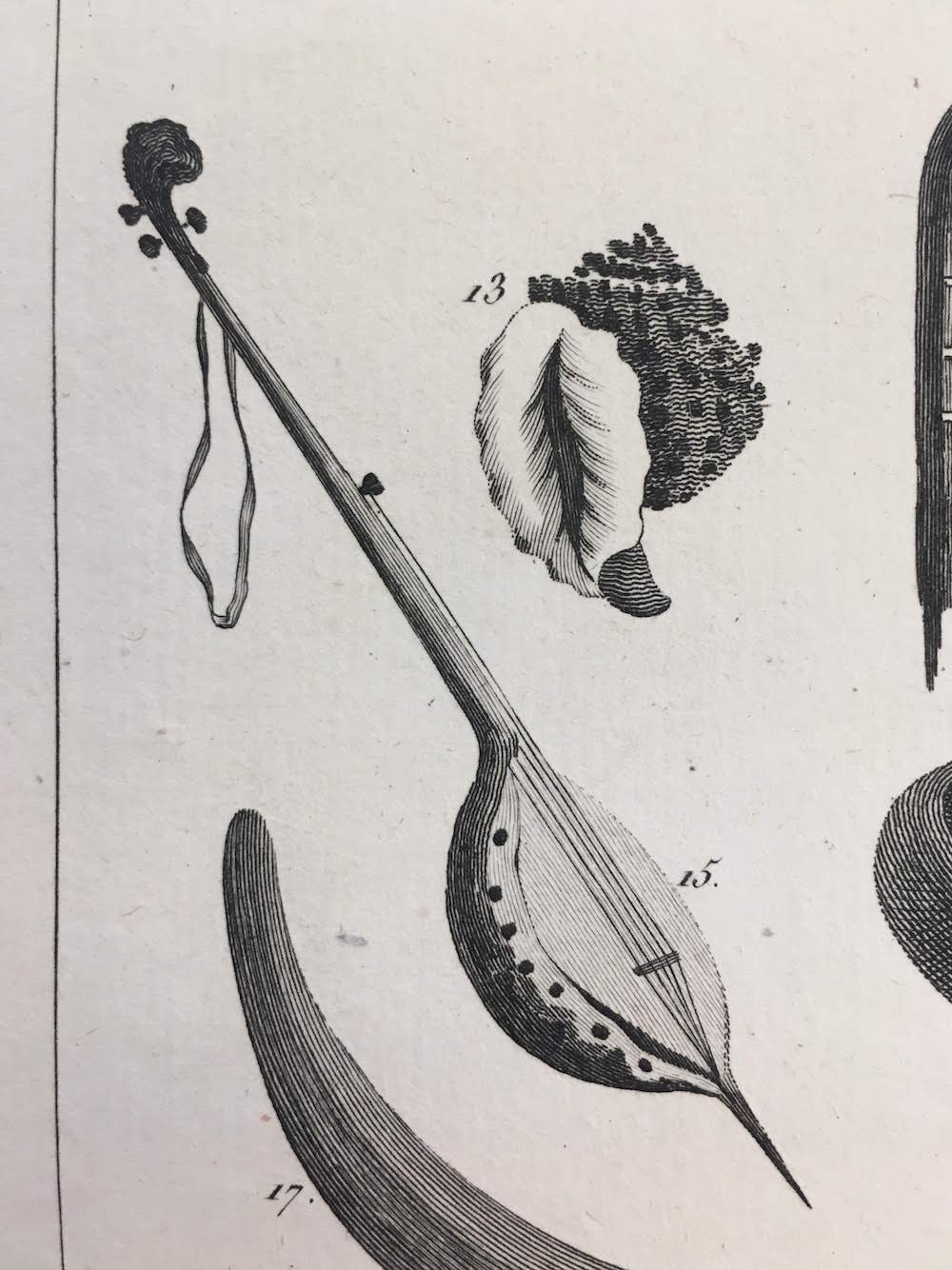

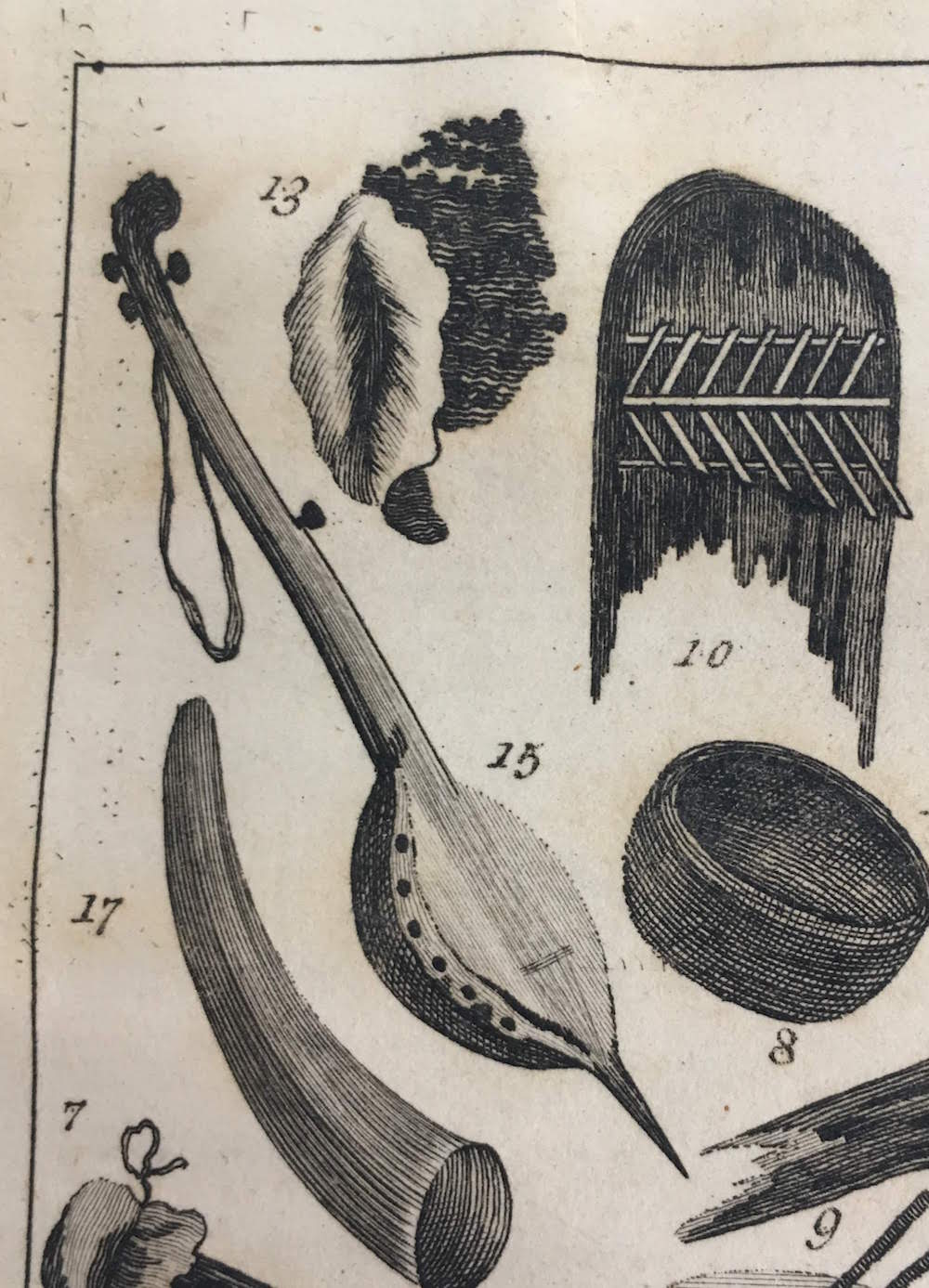

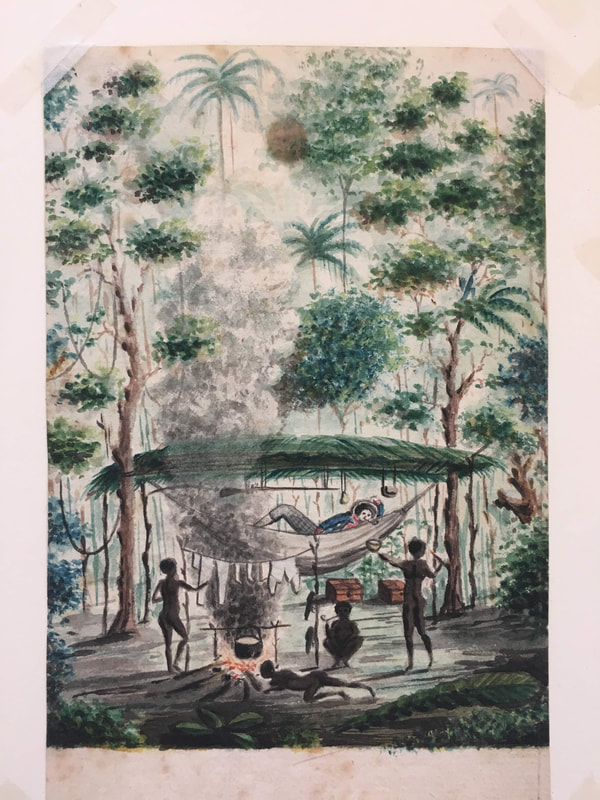

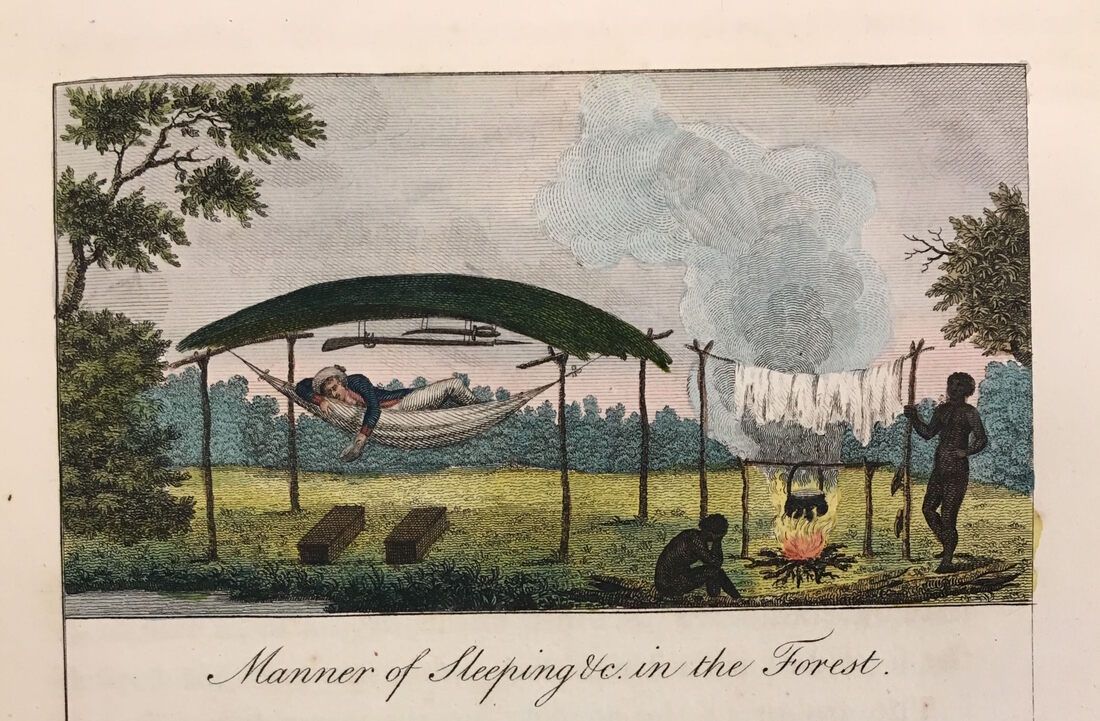

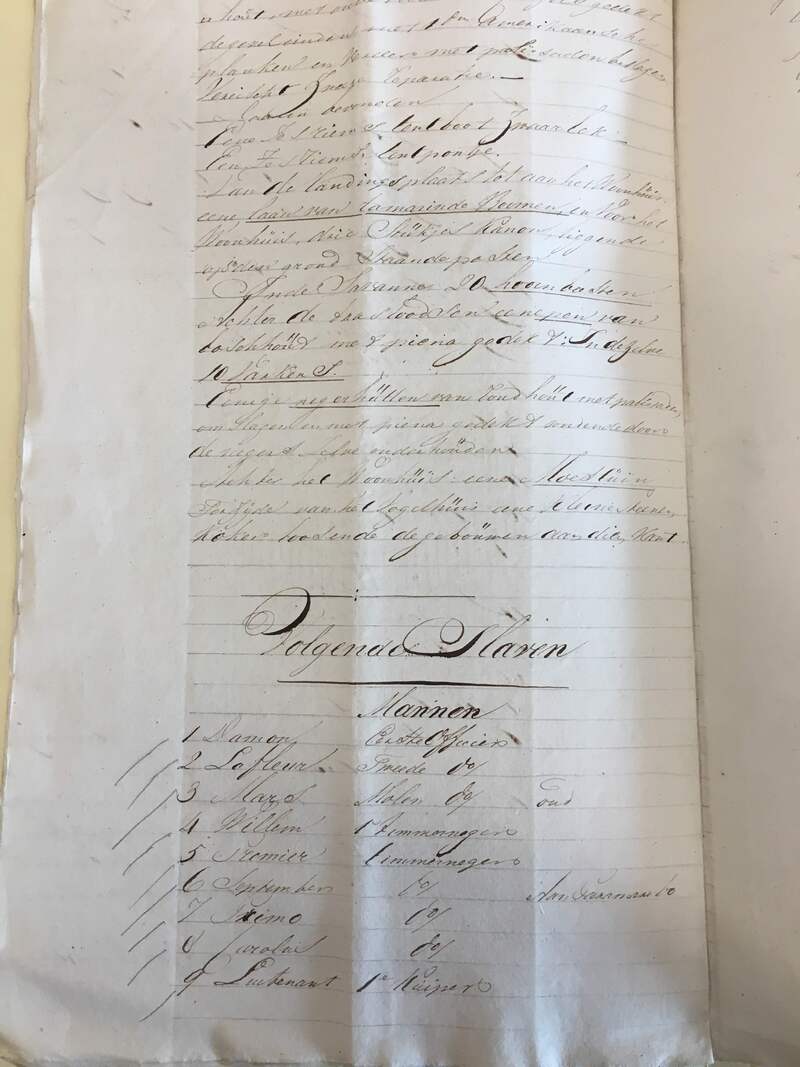

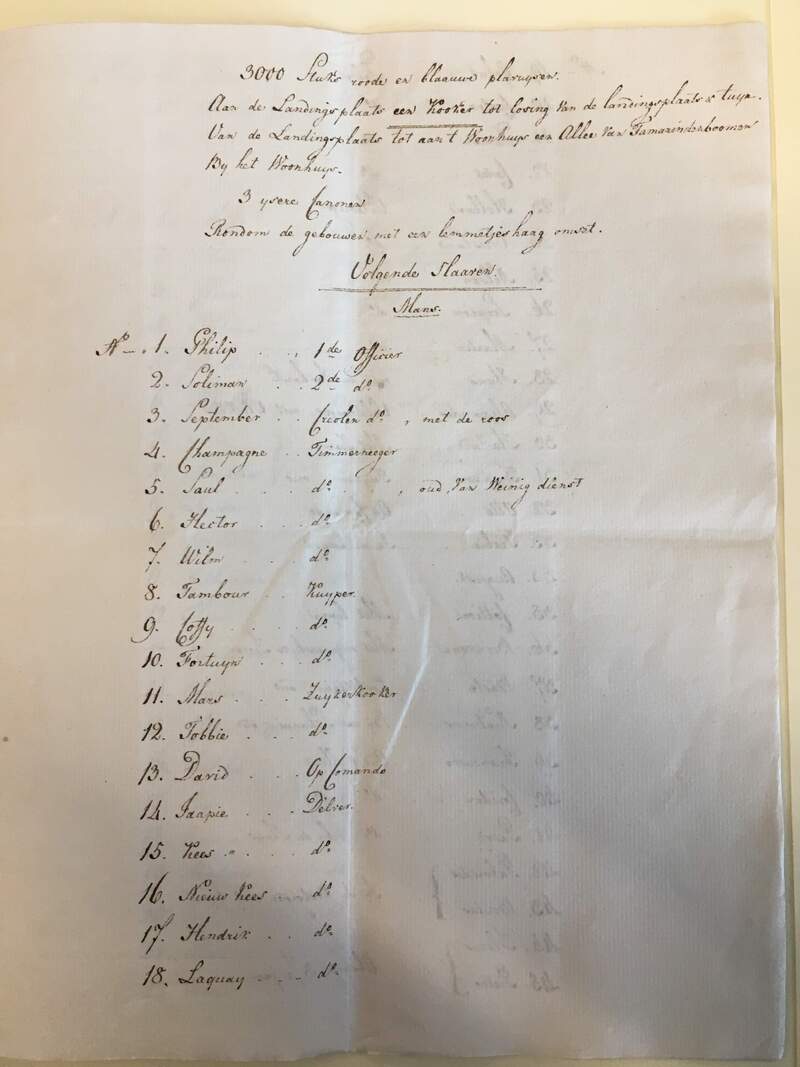

The first edition included 81 plates, based on Stedman's own drawings and watercolors. He provided his watercolors and drawings to the engravers, who made plates that became prints in the book. Below is one of his watercolors of a forest scene, and the engraver's version Unfortunately, Stedman's drawing or watercolor the engraver used to create the image of the Creole Bania is lost. One possibility, however, might be that the engraver used the actual instruments Stedman collected in Suriname to create the drawing. We know Stedman brought back the Bania, but we don't know how it ended up at in the collections of what is now the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, where it's now on permanent display as part of the Tropenmuseum's exhibit "Afterlives of Slavery." When Richard and Sally Price re-discovered the instrument in the 1970s, it was labeled "Creole Bania," but in the Asian department's storage. Even though it didn't look like the engraving in Stedman's book, they knew it was the instrument he collected. So why do the instrument and the engraving look so different? The engravers may have been looking at a sketch or watercolor and not the actual instrument, and didn’t have enough detail to faithfully recreate the instrument. Or (what I think is more likely), they let their white supremacy get in the way. They thought, a handmade instrument by a Black person in Suriname had to be “crude,” “primitive,” or “simple.” We don’t know who made the Creole Bania or how Stedman or the museum in the Netherlands got it. (I’ve got some theories but I’ll leave those for another day.) But it was very likely made by an enslaved man with a lot of woodworking experience. I haven’t seen the Creole Bania in person, but I did see the Panja, a second early banjo from Suriname. Banjo maker Pete Ross tells me that both have an incredible amount of intentionality. The Bania has an ornately carved headstock, beading around the edge that requires a specialized tool, and parts that have been smoothed with a hand plane. Whoever made it had access to these tools and knew how to use them well. Even the construction of the neck entering the calabash meant something. To say that gourd- or calabash-bodied early banjos are crude or primitive is a reflection of the white supremacy that lives on in our thoughts and words. In the collections of the De Mey van Streefkerk Papers at the James Ford Bell Library, I found evidence of how much the planation owners literally valued woodworkers. The Dutch family owned plantations and people to work on those plantations. In an inventory of the enslaved, men named Champagne, Saul, Hector, and William are listed as carpenters. In Dutch, the word “Timmerneger” designated enslaved Black woodworkers and carpenters who lived on the plantation. These men were highly skilled and highly valued. Perhaps it was one such woodworker who created the Creole Bania.

2 Comments

Ed Christian

6/26/2023 11:02:55 am

I’ve read Stedman (John’s Hopkins, 1992 edition). Thanks for the closeups of the banjo etching. One thing that may be worth noting is that the headstock seems to be the beginning of the root of a sapling carved into the neck, not a fancy carving. That would help prevent splitting of the neck and perhaps improve the sound. That etching is beyond question banjo-like.

Reply

Tony Thomas MFA

9/24/2023 08:43:45 pm

No one has shown there were banjos in Africa. Banjo researchers from Europe, North America, Africa, and the Caribbean thought they would find banjos in Africa that were not the result of the influence of banjos brought from the Americas or from Europe once banjo entertainers from England and other European countries began to bring banjos to Africa in the mid 19th century.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed