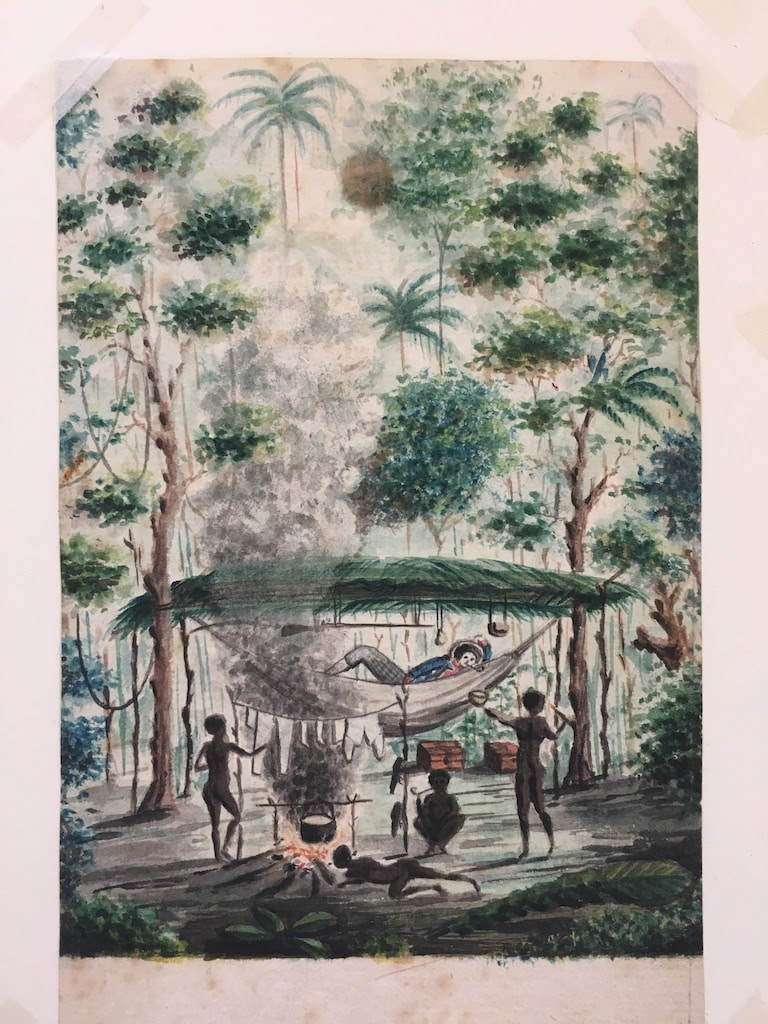

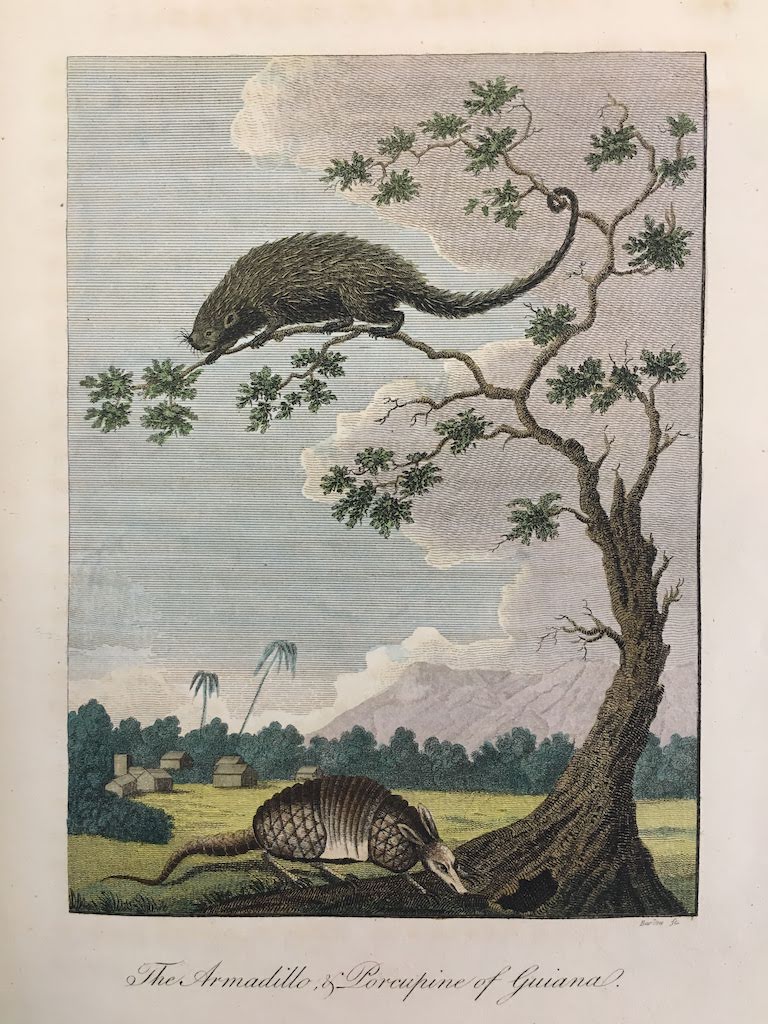

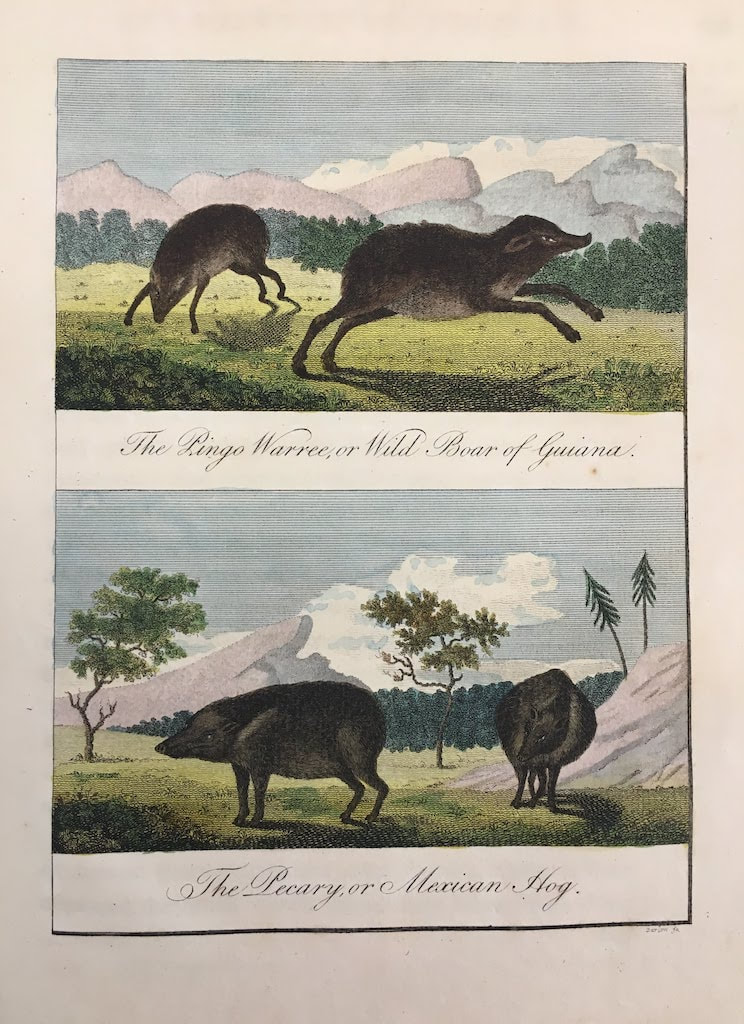

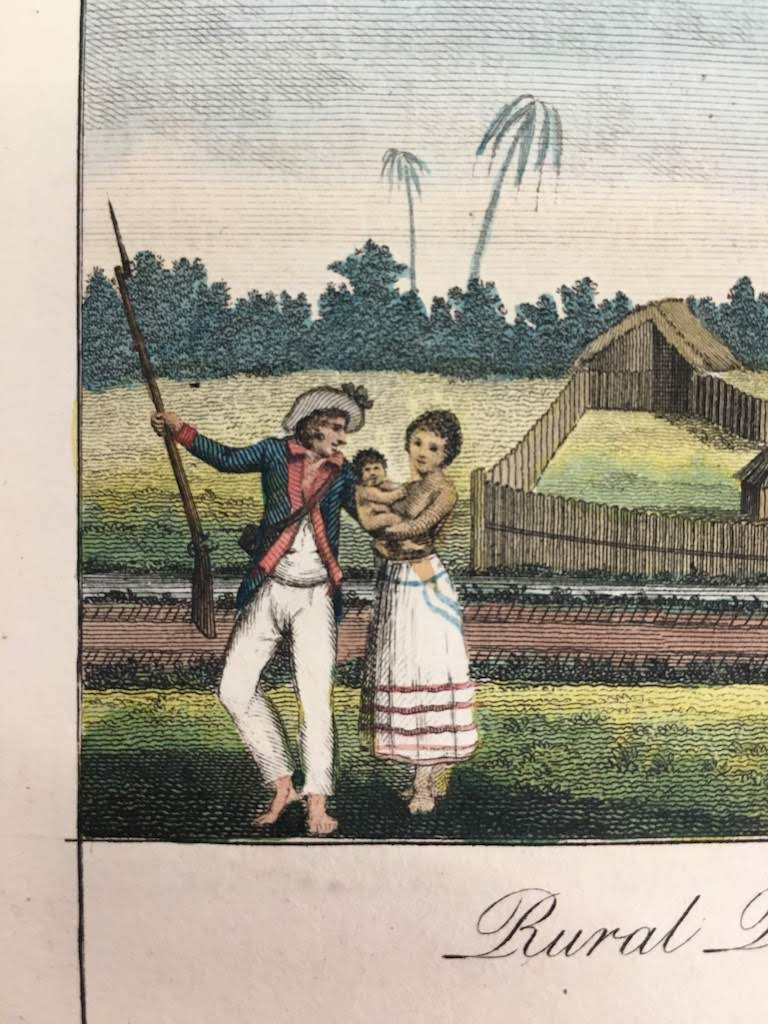

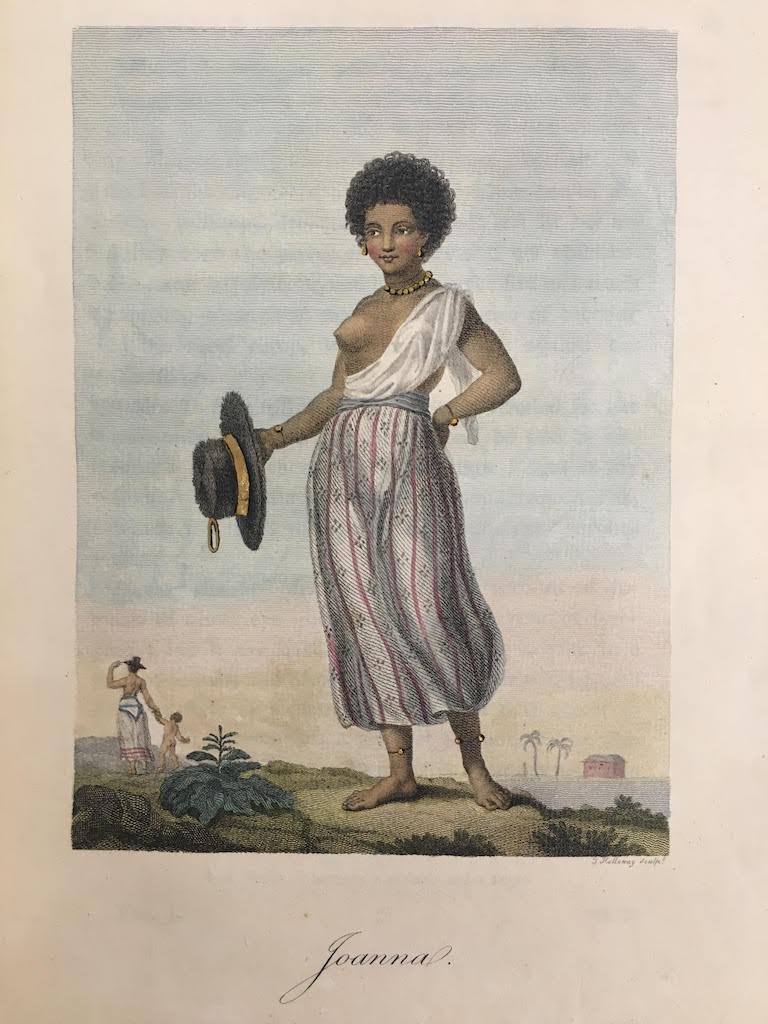

The other remaining drawings done by Stedman are not labeled, so it’s hard to know exactly what they are. Here is Stedman’s drawing of an animal, with some possibilities from the published book of what they could be… His book also includes two engravings of Joanna, although we don't know if these were copied from his drawings of her or if they were just using the descriptions he wrote.

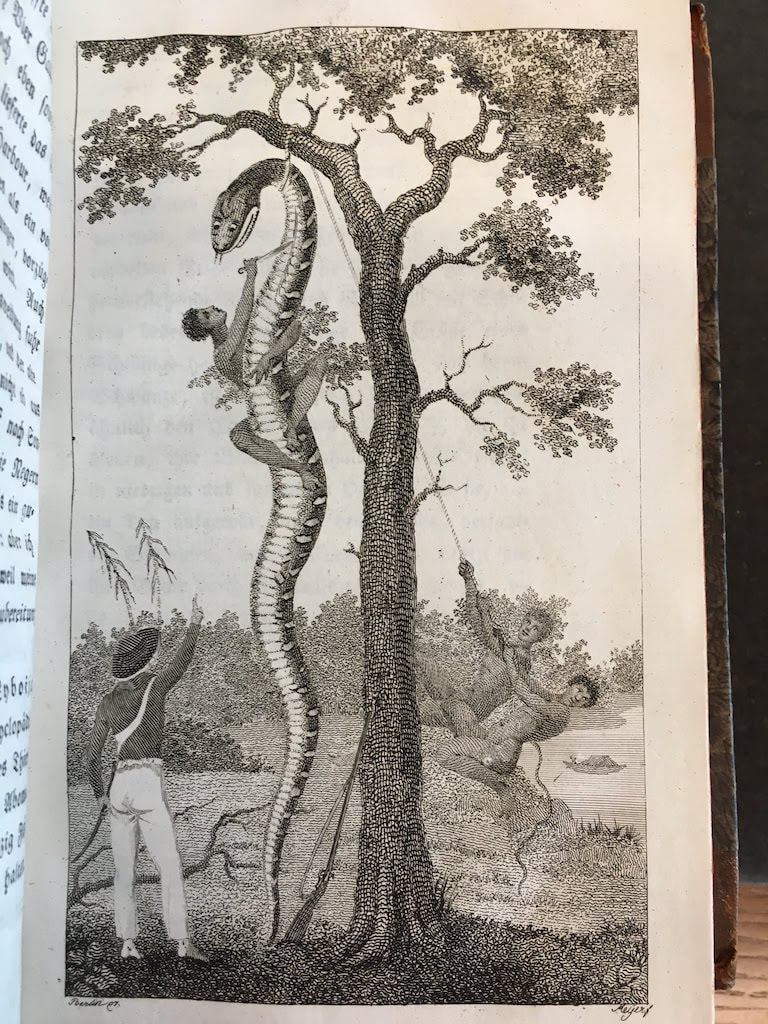

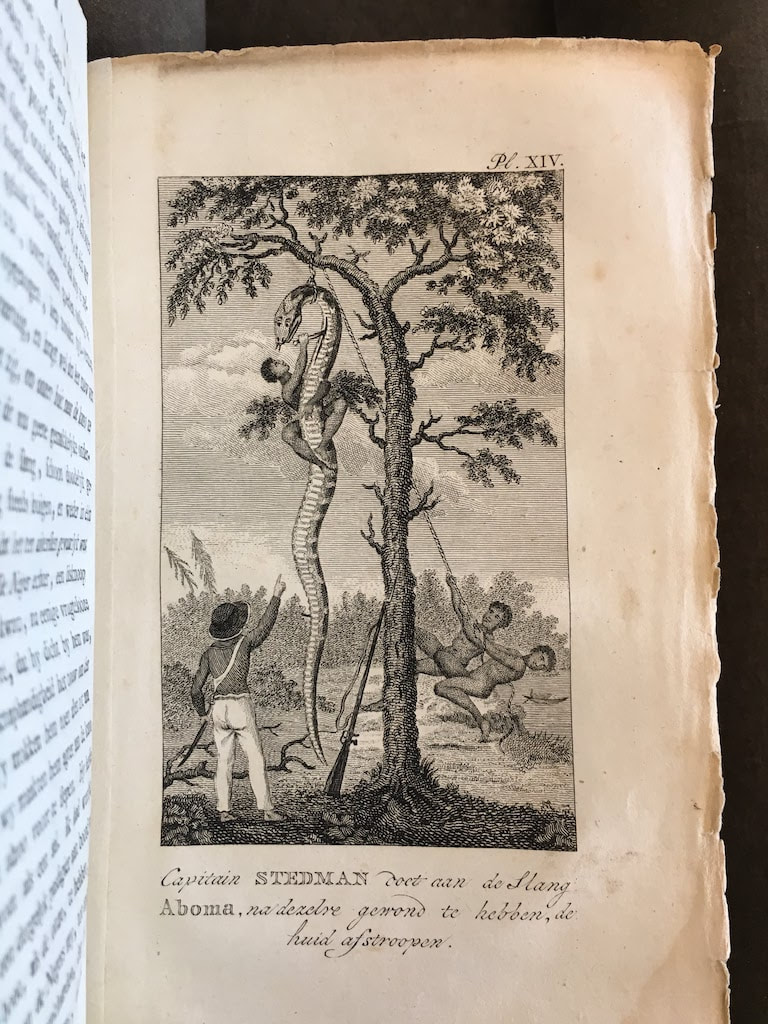

While the first English edition of Stedman’s book includes hand-colored plates, the second edition plates are uncolored, and the translated editions all have fewer plates (between eight and forty-six). All four of the images below show the aboma constrictor that Stedman writes about, but as the image travels from the original (on the left), to German (second from left), to Dutch (second from right), to the Italian (on the right), you can see how the image changes with each particular engraver's style and skill. The changes you see remind me that while historical images can be so informative, they are also problematic--and not only because of racism or white supremacy that impacted how an artist chose to depict something. Almost all of the translations with illustrations have the “Musical Instruments” plate, where you can see a roughness to the drums that doesn't reflect how they are actually constructed. For example, the open ends of the drums look like broken logs and the skins are held on with strings, which both isn't practical or how the people who made the instruments would construct or treat an important object. Is this because of how the engraver assumed the instruments of the enslaved would be made? Is this because he was making the engraving based on descriptions and not the actual instruments? In this case (and in many cases), we don't know. All images are courtesy of the James Ford Bell Library, University of Minnesota Libraries. Some of these books are available from Archive.org (https://archive.org/search.php?query=john%20gabriel%20stedman). [1] Richard and Sally Price, Stedman’s Surinam: Life in an Eighteenth Century Slave Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), xl. [2] Ed Simon, "William Blake, Radical Abolitionist," JSTOR Daily, June 5, 2019 https://daily.jstor.org/william-blake-radical-abolitionist/ [2] John Gabriel Stedman 1790 Manuscript, James Ford Bell Library, University of Minnesota, 760. [3] Stedman’s Surinam, 301. This is part of Banya Obbligato, a series of blog posts relating to my book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. While integrally related to Well of Souls, these posts are editorially and financially separate from the book (i.e., I’m researching, writing, and editing them myself and no one is paying me for it). So, if you want to financially support the blog or my writing and research you can do so here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed