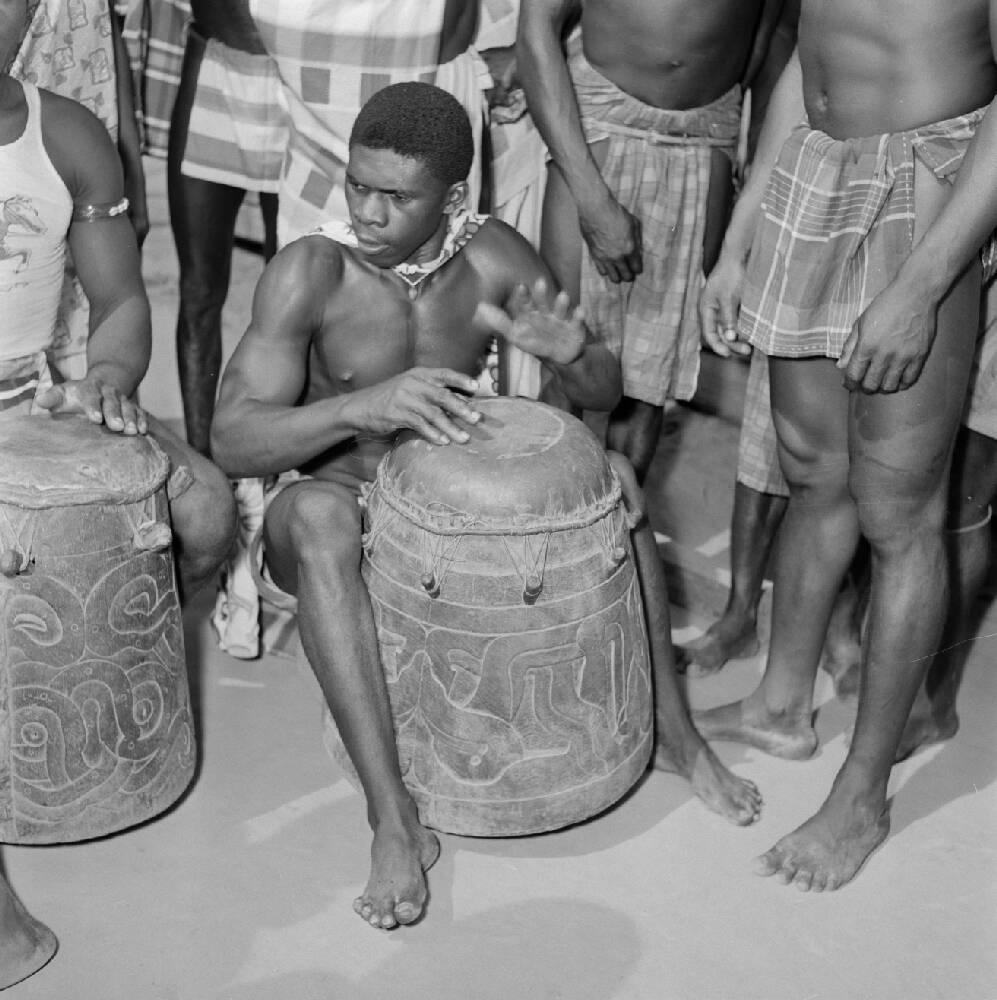

But as I flipped through the book, I was keeping an eye out for photos and descriptions of music, dance, instruments, and religion. While he took photos in Paramaribo, Van de Poll also went further into the interior of the colony and was clearly captivated by Maroons. They were the descendants of people who had escaped enslavement starting in the 1600s and formed autonomous communities in the jungle--and were who John Gabriel Stedman was sent to fight in the 1700s. Today, there are six groups of Maroons in Suriname (although where they live also crosses the border into French Guiana): the Ndyuka, the Saramaka, the Matawai, the Aluku, the Paramaka and the Kwinti. At a Maroon celebration before 1951, Van de Poll described the musicians: “On my left in an open shed was the ‘band’: a number of tall drums held between the knees and beaten with both hands, some ‘shakers,’ calabash shells filled with some hard dried fruit stones, and a very simple percussion instrument, consisting of just a board of very hard wood beaten by a big drumstick of the same hard wood in syncopation with the rhythm theme” [1]. The women wore “joro-joros” around their ankles, “fibers plaid with a number of hard shells attached.” In 1855, the Surinamese lawyer and amateur folklorist H.C. Focke wrote that the joro-joro was “a string of shells split in half and strung together with the fruit of the Thevetia nerifolia” [2]. Hans Sloane also observed this type of rhythm instrument in Jamaica in 1687, and similar instruments are worn by Kongo, Igbo, and Fon dancers in Africa. In “Afro-Surinamese Music,” Ponda O’Bryan writes that “awasa and songé” dancers of Ndyuka Maroon tribe (who he calls Aucaners) use the rattles to add “rhythmic accents to their steps” [3]. Van de Poll described other dances: “Clearly everybody was ‘playing his role’ and the ‘Awasa’ dances, sheer pleasure and enjoyment, have nothing to do with the ‘Winti’ or spirit dances where such a prominent part is taken by the person who completely identifies himself with the spirit and tries by his own extortions and thorough exhaustion to drive the spirit from among his people.” Any description of Winti dances, even a short one like this, was of interest to me. But as I was reading, it felt like he should have been illustrating these descriptions with photos. Then, I noticed small tear marks near the binding. I wrote to myself, “Photos of dancing have mainly been ripped out of the book.” What did they show? What was I missing?Then, my next thought was, “Surely, these photos have to exist somewhere else.” This is when it was good that Van de Poll worked for the royal family. The National Archive in the Haag has about 40,000 of his negatives, including over 3,300 from Suriname. So, my only choice was to flip through page after page online, looking for the dance photos. And it was so worth it. In two images from 1955 (after the book was published), Van de Poll captured Maroon drummers and dances in Moengotapoe, a village east of Paramaribo near the border to French Guiana. The drums have intricate carvings on the side and the skin head is held down with large wooden dowels, very similar to many African drums. The men and women dance with joro-joro rattles around their ankles, a percussion instrument similar to one from the 1800s collected in Central Africa, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. But, as Richard and Sally Price point out in Maroon Arts, Maroon groups "cannot be said to have shared any particular African culture" both because they came from many places across West and Central Africa and had from the beginning come into contact with the "newly developed culture of Suriname slaves," but did have similar "socio-cultural forms" on which their new societies and cultures were based [4]. In most 20th century accounts I read of dances in Suriname, the only instruments mentioned are drums and rattles. In Afro-American Arts of the Surinam Rain Forest, the Prices write about the importance of drumming: “Different drum choirs and particular styles of drumming mark each of a large number of specialized performance contexts — e.g. Rites for forest spirits, snake gods, warrior gods or early ancestors; various stages of funeral rites; and a variety of secular settings. Each such style of drumming is specialized, sometimes involving formal apprenticeship" [5]. In 1943, Philip Hanson Hiss saw koromanti and winti dances and commented that they used drums and a piece of iron for percussion, and were "interesting because of their frenzied tempo and because they often lead to trance rather than for their choreography” [6]. The role of the drummer was in fact to "[persuade] waiting gods and spirits to join villagers through possession," according to the Prices [7]. The instrument that John Gabriel Stedman collected in Suriname was dubbed the Creole-bania because it was associated with Creoles--people of African and European descent and not Maroons. O'Bryan doesn't mention banjos as being part of Afro-Surinamese musical traditions, but I know from the historical record that was used in religious dances in Suriname through the 20th century. And when I traveled in 2018 to a Saramaka eco-resort to explore the rain forest, our guide Alberto told us that his uncle played the "banya," as he made a strumming motion across his chest. He couldn't give us any more information, but I kept thinking that string instruments (and maybe even the banjo) could be a part of Maroon traditional music, too. Then I came across the photo above, taken during an Awasa dance in an unnamed Maroon village. I immediately spotted the men playing something that looked like guitars, and other photos showed at least five musicians playing string instruments during the dance.

Van de Poll doesn't mention these string instruments at all is his book, although maybe he did keep notes somewhere else about what he saw. I wish I knew more, and I can only say what I say a lot: more research needs to be done. It could be that this group of musicians liked the sound a string instrument added to the Awasa band, adding something contemporary to their tradition. But perhaps like many white observers throughout the musical history that I explore in Well of Souls, the musicians and dancers didn't want to tell Van de Poll much about what they were playing. Discussing "Creole Folk Music" in 1959, G.D. van Wengen writes, "As many of their [Maroon's] musical expressions and dances are connected with the religious aspect of their culture, and as at the same time they are suspicious of the intentions of the white stranger, they dislike giving information on occasions which are sacred to them" [8]. Sources: [1] Willem Van de Poll, Surinam. The Country and its People, Den Haag: W. Van Hoeve Ltd., 1951 (30). [2] H.C. Focke, “De Surinaamesche Negermuzijk,” West-Indië: bijdragen tot de bevordering van de kennis der ..., Volume 2. November 1855. [3] Ponda O’Bryan, “Afro-Surinamese Music," Surinamese Music in the Netherlands and Suriname (ed. Marcel Weltak, trans. by Scott Rollins), Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2021 (15). [4] Sally and Richard Price, Maroon Arts: Cultural Vitality in the African Diaspora, Beacon Press: Boston, 1999 (280-281). [5] Sally and Richard Price, Afro-American Arts of the Suriname Rain Forest. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980 (179). [6] Philip Hanson Hiss, Netherlands America: The Dutch Territories in the West. Dell, Sloan and Pearce: New York, 1943 (38). [7] Price, Afro-American, 179. [8] G. D. van Wengen, "The Study of Creole Folk Music in Surinam," Journal of the International Folk Music Council, Vol. 11, 1959, (45-46). This is part of Banya Obbligato, a series of blog posts relating to my book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. While integrally related to Well of Souls, these posts are editorially and financially separate from the book (i.e., I’m researching, writing, and editing them myself and no one is paying me for it). So, if you enjoyed this as much as a cup of coffee, you can throw me a couple of bucks here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Come in, the stacks are open.Away from prying eyes, damaging light, and pilfering hands, the most special collections are kept in closed stacks. You need an appointment to view the objects, letters, and books that open a door to the past. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed